Daniela Pilková, a student at the Prague University of Economics and Business, mail: pild03@vse.cz

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly reshaping marine biology by enabling researchers to process and interpret large volumes of oceanographic data with unprecedented efficiency. Traditional research methods, such as diver surveys and boat-based sampling, face significant limitations due to physical inaccessibility, high operational costs, and the large volume and complexity of the marine data. This essay examines how AI, in combination with external data sources such as satellite imagery, sensor networks, and citizen science contributions, has reshaped research practices, enhanced ecosystem monitoring, and facilitated predictive modeling in marine environments. Drawing on a critical review of the current literature and applied case studies, this study identifies key AI applications, including automated species recognition, real-time environmental monitoring, and large-scale data integration. The findings suggest that AI-driven approaches not only improve the efficiency and scope of marine research but also alter the ways in which knowledge is produced, validated, and communicated.

Keywords

Artificial intelligence, marine biology, data sources, ocean data, machine learning, knowledge production, environmental monitoring

1. Introduction

In recent years, the term AI, or artificial intelligence, has become a part of our daily vocabulary, and it is hard to imagine life without it. Today, AI is extensively utilized across all fields, including marine biology. Machine learning and AI provide new insights into ocean exploration, monitoring marine ecosystems and organisms, and even supporting efforts to clean plastic debris from the ocean.

The use of AI and external data offers a significant advantage over traditional methods, as the latter often fall short. Traditional techniques encounter numerous challenges that can be effectively overcome using AI.

The first challenge is the human body. Diving to great depths is extremely dangerous for humans because of the intense pressure and lack of natural light, which makes these areas largely inaccessible. This is why more than 80 percent of the world’s oceans remain unexplored and unmapped (NCEI, 2018). Conducting research under such conditions requires enormous resources and time and, most importantly, poses significant risks to human life (Cleaner Seas – pt1, 2025). Another challenge is that many changes and phenomena in the ocean are not visible to the human eye. AI can effectively address this issue.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, conventional methods, such as diver surveys and boat-based sampling, require substantial time, resources, and financial investment; however, they remain limited to relatively small, localized areas. Therefore, achieving a comprehensive understanding of marine ecosystems requires large-scale models, which can be facilitated by AI. Moreover, the rapid pace of environmental change makes it challenging to interpret data manually, further highlighting the advantages of AI-assisted analysis (Amazinum, 2023).

The next challenge is the scale of the world’s oceans, combined with their variability. This requires sophisticated interpretations of biological, chemical, and physical interactions. Therefore, when using traditional data processing methods, the information obtained is often incomplete and ambiguous (Cleaner Seas – pt2, 2025).

Another problem lies in the size of the data set. A large ocean requires large amounts of data. Researchers collect large quantities of visual data to observe ocean life. How can we process all this information without automation? Machine learning provides an exciting pathway forward.- MBARI Principal Engineer Kakani Katija (MBARI, 2022). AI plays a crucial role in analyzing these data and identifying patterns.

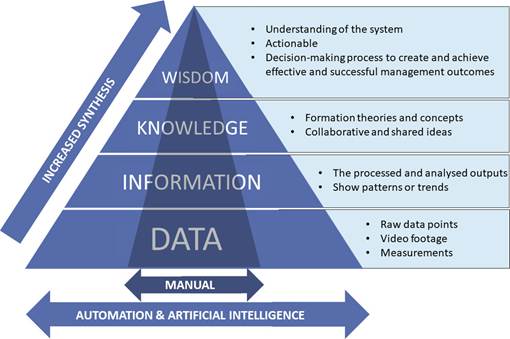

The implementation of AI-driven automated methods for data collection and processing enables researchers to expand the scope, resolution, and breadth of conservation studies. By providing managers with more comprehensive information, it enhances their ability to share knowledge and understand the target ecosystem. When combined with advanced machine learning techniques for analysis and prediction, these methods can lead to a deeper understanding of the system and improve the capacity to manage degraded ecosystems effectively. Eliminating the processing bottleneck also accelerates the transformation of data into actionable insights, allowing management decisions to be made more quickly and efficiently (Ditria et al., 2022).

This essay aims to examine in detail how Artificial Intelligence, together with the growing availability of external data sources, has transformed marine biology research. It seeks to highlight the ways in which these technologies are currently being applied, the benefits they bring to the study of marine ecosystems, and how they shape the future of ocean research.

2. AI in Marine Monitoring

2.1. Monitoring, categorizing and counting fish

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has fundamentally reshaped the way marine biologists monitor fish populations. Traditional monitoring approaches rely heavily on invasive and laboriousmethods, such as capturing, sedating, and tagging fish to track movement patterns and population trends. Halvorsen notes that using these conventional techniques, researchers often tagged between 3,000 and 5,000 individuals per year—procedures that not only required considerable effort but also imposed physiological stress on the animals (Innovation News Network, 2022). As he explains, “With Artificial Intelligence, we avoid having to catch, sedate, and microchip the fish. This means that we can be less intrusive to marine life and still obtain more information” (Innovation News Network, 2022). AI-enabled monitoring therefore represents a major ethical and methodological improvement by reducing the need for direct animal handling and generating richer and more continuous datasets.

A parallel limitation of earlier monitoring methods involved the manual review of extensive underwater video footage to count fish, estimate body size, and identify species a process prone to human error and constrained by time (Amazinum, n.d.). AI-driven systems embedded in underwater cameras, sonars, and sensor technologies can now automate these tasks with high precision. Modern algorithms can detect, count, and classify fish and identify individuals in species such as salmon, cod, corkwing wrasse, and ballan wrasse based on unique morphological patterns (Goodwin et al., 2022).

These practical developments are supported by advances in deep learning (DL). In real underwater environments, videos often contain multiple individuals within a single frame, which renders standard classification insufficient. As Goodwin et al. (2022) outlined, effective AI monitoring systems must combine object detection with classification. Object detection models, such as those in the YOLO family, first discriminate and isolate each fish within an image before species-level classification is applied. Because widely used training datasets (e.g., Coco or ImageNet) include few marine images, high-performance detection requires custom datasets of fish in their natural environments, making data collection and annotation central to system development (Goodwin et al., 2022).

In video-based research, DL enables automated object tracking. Tracking algorithms can follow individual fish across consecutive frames to extract behavioral metrics, such as movement trajectories and swimming speed, or to prevent repeated counting of the same animal. Tracking solutions typically integrate detection with association and dynamic estimators, such as Kalman filters, although emerging fully integrated DL-based tracking models can perform multi-object tracking in a single step (Goodwin et al., 2022). These approaches reduce the need for manually tuned mathematical models and can provide a more homogeneous system performance.

Applied projects along the Skagerrak coast have demonstrated how these technical capabilities can be translated into improved ecological monitoring. AI systems deliver continuous observations without fatigue, offering a higher temporal resolution and greater data reliability than manual review. Initiatives such as the Coast Vision project illustrate how automated analysis can provide near-real-time insights into coastal ecosystem health and support more responsive management decisions (Innovation News Network, 2022).

Collectively, these advancements demonstrate that AI has become a foundational technology in marine ecological monitoring. By increasing efficiency, accuracy, and ethical standards, AI-enabled systems allow researchers to quantify, classify, and track marine organisms with unprecedented detail and minimal disturbance, ultimately opening new opportunities for long-term behavioral and population dynamics research (Goodwin et al., 2022).

2.2. Plankton monitoring

Plankton are a diverse group of organisms, ranging from submicron sizes to several centimeters, and form the base of marine food webs. Certain species serve as bioindicators of ecosystem health, whereas others can cause harmful algal blooms with ecological and economic impacts. Therefore, monitoring seasonal, interannual, and spatial changes in plankton abundance and composition is central to coastal management.

Image-based monitoring has become a standard approach that generates large datasets requiring automated analysis. Deep learning (DL) enables the efficient detection, classification, and quantification of plankton, reducing the need for time-consuming manual processing and minimizing human bias (Goodwin et al., 2022). Traditional machine learning methods, such as support vector machines and random forests, achieved 70–90% accuracy but required manually defined features and struggled with rare or cryptic species. CNNs have largely overcome these limitations by extracting features directly from images and achieving accuracies of up to 97% on large datasets (Goodwin et al., 2022).

DL systems can be applied in situ using instruments such as Imaging FlowCytobot, VPR, and IISIS, or in the laboratory with systems such as FlowCam and ZooCam (Goodwin et al., 2022). They segment images into individual organisms, classify them into taxonomic or functional groups, and extract key features, such as size and shape. Tracking temporal and spatial dynamics using these approaches produces data comparable to those obtained using traditional microscopy, while enabling long-term, high-resolution monitoring of community composition, size spectra, and bioindicator species (Goodwin et al., 2022).

Although DL cannot fully replace taxonomists for difficult identifications, it reduces manual labor and allows for broader and faster analyses. The integration of complementary datasets offers the most effective strategy for coastal plankton monitoring. Overall, AI-driven monitoring enhances accuracy, efficiency, and ecological insight, providing a scalable solution for understanding and managing plankton communities (Goodwin et al. 2022).

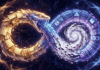

2.3. Monitoring whales

Monitoring whale populations is essential for understanding ecosystem dynamics; however, traditional manual methods, such as retrieving long-term acoustic recordings, generating spectrograms, and visually scanning them for whale calls, are labor-intensive, subjective, and often impractical for long-term studies (Goodwin et al., 2022). AI and deep learning (DL) provide scalable alternatives by enabling the automated identification, classification, and tracking of whale calls across large spatial and temporal scales (Jiang & Zhu, 2022).

Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been successfully applied to detect humpback whale songs and distinguish relevant signals within massive acoustic datasets. Similarly, AI pipelines can integrate visual and acoustic data to extract multiparameter ecological information, including species presence, spatial distribution, and temporal dynamics (Goodwin et al., 2022). Region-based CNNs, transformer networks, and recurrent architectures, such as long short-term memory networks, allow precise localization and tracking of calls, overcoming the limitations of standard CNNs that provide only “presence” information without temporal resolution (Jiang & Zhu, 2022).

Figure 1: An approach to sperm whale communication (source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004222006642#bib131)

AI-based monitoring also reduces manual effort, enabling continuous and noninvasive data collection. By automating detection and classification, researchers can track population trends, seasonal migrations, and behavioral patterns more efficiently and accurately than with traditional methods. The integration of DL techniques with PAM recordings provides a robust and widely applicable framework for monitoring whale populations, offering richer datasets for management and conservation decisions (Goodwin et al., 2022; Jiang & Zhu, 2022).

2.4. Monitoring seal population

Monitoring seal populations is essential for assessing marine ecosystem health; however, traditional approaches, such as manually counting individuals in survey photographs, are slow, labor-intensive, and prone to human error. Historically, analysts required nearly an hour to count seals in 100 images, limiting the temporal and spatial scales of ecological monitoring. Recent AI approaches have dramatically improved this process: deep-learning models can now analyze the same number of images in under a minute, without requiring manual pre-labelling of individuals, thereby accelerating population assessments and enabling long-term trend analysis (Simplilearn, 2023; Amazinum, 2023).

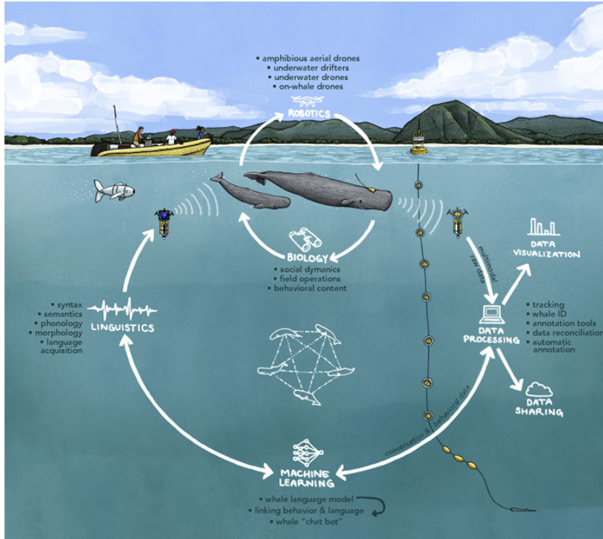

Beyond population counts, seals are ideal candidates for individual-level monitoring because they aggregate at haul-out sites and can be photographed from a distance. Thus, computer vision systems provide a scalable, noninvasive tool for ecological research. The FruitPunch AI initiative has developed a fully integrated pipeline for seal detection and identification, combining face detection, facial recognition, and a graphical interface for field biologists (FruitPunch AI, 2023).

The face detection component is centered on migrating legacy dlib-based methods to modern architectures, such as YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and RetinaNet. Through extensive experimentation with model versions, sizes, and training epochs, the YOLOv8s model trained for 45 epochs exhibited the best performance. The model accuracy was further improved by rigorous dataset preparation: the team consolidated 384 labelled harbor seal images with additional publicly available fur seal datasets and applied augmentations such as flipping, exposure shifts, blur, and noise. The final system achieved over 15% improvement in detection accuracy and substantially reduced the computational overhead required for future retraining (FruitPunch AI, 2023).

For individual identification, FruitPunch AI evaluated multiple approaches, reflecting the absence of a clear, best-performing model at the outset. These include HOG-based feature extraction paired with stochastic gradient descent, SVM classifiers applied to flattened image vectors, VGG16 with cosine similarity for feature-space comparison, EfficientNetB0 with a lightweight CNN backbone, and Siamese networks (ResNet50/RegNet16) designed to learn similarity distances between images.

Figure 2: VGG16 with cosine similarity (source: https://www.fruitpunch.ai/blog/understanding-seals-with-ai)

Closed-set identification (matching a seal to known individuals) and open-set verification (evaluating the similarity between an unknown seal and the database) were implemented. Although the Siamese network performed well, traditional CNN-based classification models yielded higher overall accuracy, guiding the decision for integration into the final system (FruitPunch AI 2023).

Taken together, these developments demonstrate how modern AI tools can significantly improve the efficiency, accuracy, and scalability of marine mammal monitoring methods. Automated detection and recognition allow researchers to study seal population dynamics more frequently and with greater precision while reducing the manual burden of photographic analysis (Simplilearn, 2023; Amazinum, 2023; FruitPunch AI, 2023).

2.5. Debris monitoring

Plastic pollution is one of the most severe environmental threats to marine ecosystems, with global plastic production exceeding 430 million tons per year and up to 11 million metric tons entering the ocean annually (Amazinum, 2022). As these debris flows intensify, AI-based technologies have become increasingly essential for enabling continuous, scalable, and cost-effective monitoring compared to manual surveys and trawl-based assessments (Amazinum, 2022). Recent developments have demonstrated that machine learning, deep neural networks, autonomous imaging systems, and satellite-based computer vision collectively form a robust technological framework for detecting and mapping marine debris across diverse ocean environments (Amazinum, 2022; Wageningen University, 2023; The Ocean Cleanup, 2021).

Satellite imagery can now be analyzed automatically using deep-learning detectors that score the probability of marine debris at the pixel level. Researchers at Wageningen University and EPFL trained a detector on thousands of expert-annotated examples so that the model can identify floating debris in Sentinel-2 images even under difficult conditions (cloud cover, haze), thus supporting near-continuous coastal monitoring when combined with daily PlanetScope data (Wageningen University, 2023). When sentinel and nanosatellite images capture the same object within minutes, the pairwise observations can reveal short-term drift directions and help improve debris-drift estimates (Wageningen University, 2023). The Wageningen/EPFL work is explicitly positioned within the ADOPT (AI for Detection of Plastics with Tracking) collaboration and is intended to feed operational partners (including Ocean Cleanup) working on detection and removal workflows (Wageningen University, 2023).

Complementing satellites, vessel-based optical surveys processed by AI provide higher-resolution, georeferenced maps of macroplastic concentrations. The Ocean Cleanup developed an object-detection pipeline trained on ~4,000 manually labelled objects (augmented to ~18,500 images) from past expeditions and applied it to >100,000 geotagged GoPro photos collected during a System 001/B mission; the algorithm produces GPS-referenced detections, projects object size and distance, and computes numerical densities per transect to map macroplastic (>50 cm) concentrations (The Ocean Cleanup, 2021). The Ocean Cleanup team ran their model on hundreds of gigabytes of imagery (the processing took days), verified AI suggestions by human operators, and used verified detections to generate concentration maps that track increases in density toward the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (The Ocean Cleanup, 2021). These vessel-based maps are presented as a practical, repeatable alternative to costly trawl surveys and aerial counts, enabling routine monitoring from ships. (The Ocean Cleanup, 2021).

Figure 3: Typical detections by the algorithm. Several verified objects after manual sorting and elimination of duplicates (source: https://theoceancleanup.com/updates/using-artificial-intelligence-to-monitor-plastic-density-in-the-ocean/)

At smaller, operational scales, AI also supports autonomous and semi-autonomous cleanup systems. Machine-vision-powered robotics such as Clearbot use onboard cameras and trained detection models to locate visible debris in turbulent waters and direct collection gear; other initiatives (e.g., solar-powered skiffs and automated surface vehicles) combine detection with navigation and collection to remove items once identified (Amazinum, 2022). AI is also used upstream: community and municipal projects apply image-recognition tools to classify waste for recycling and to assign material value, thereby improving collection efficiency and reducing the amount of waste entering waterways (Amazinum, 2022).

Taken together, the three strands — satellite detectors for regional surveillance, vessel-based object detection for high-resolution mapping, and AI-enabled robots and local image-classification tools for removal and source control — form a layered AI toolkit for ocean debris work. This multi-platform approach improves detection under adverse conditions (clouds, haze, short observation windows), provides geolocated concentration maps to prioritise cleanup effort, and supplies input to drift models that predict where debris will move next — all of which are critical for effective, targeted removal and for understanding the ecological distribution of macroplastics (Wageningen University, 2023; The Ocean Cleanup, 2021; Amazinum, 2022).

3. Machine Learning Techniques

3.1.Predicting of Ocean Parameters

Accurate prediction of key ocean parameters such as sea surface temperature (SST), tide levels, and sea ice extent is essential for understanding climate dynamics, managing marine ecosystems, and supporting maritime activities. Traditional statistical and numerical models often struggle to capture the complex spatiotemporal dependencies inherent in these parameters, particularly when attempting to forecast across large spatial domains or over extended time periods. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL) have enabled the development of predictive models capable of addressing these challenges with improved accuracy and efficiency (Jiang & Zhu, 2022; Simplilearn, 2023).

For instance, convolutional long short-term memory (ConvLSTM) networks have been applied to SST prediction, effectively capturing both temporal evolution and spatial correlations across large oceanic regions. Experiments conducted in the East China Sea demonstrated that such models outperform traditional persistence-based and numerical forecasting methods, providing highly accurate daily SST predictions across multiple years of satellite-derived datasets (Jiang & Zhu, 2022). Similarly, neural network–based approaches can estimate tidal levels by incorporating the underlying physical and astronomical drivers of tidal dynamics, enabling the development of flexible models that can generalize across different coastal regions (Simplilearn, 2023).

Beyond SST and tides, AI models have also been employed to predict sea ice extent and dynamics in polar regions. By constructing spatiotemporal correlation networks and extracting key climatic features from historical observational data, DL models can forecast regional ice coverage with higher resolution and accuracy than conventional statistical techniques (Jiang & Zhu, 2022). More broadly, these approaches illustrate the capacity of AI to integrate heterogeneous datasets—combining satellite imagery, in-situ sensor measurements, and historical environmental records to produce predictive outputs that are both temporally and spatially precise.

The practical implications of these advancements are significant. Enhanced predictive capabilities for ocean parameters support a wide range of marine applications, including fisheries management, shipping route optimization, marine conservation planning, and climate monitoring. By uncovering underlying correlations and patterns in large-scale oceanographic datasets, AI models facilitate proactive decision-making and provide the scientific basis for adaptive strategies in the face of climate variability (Jiang & Zhu, 2022; Simplilearn, 2023). As AI technologies continue to advance, integrating more sophisticated architectures—such as hybrid models combining convolutional neural networks, recurrent networks, and support vector machines promises to further improve predictive accuracy and extend the range of operational applications in marine science.

3.2.Modeling of Deep-Sea Resources

Deep-sea navigation remains one of the most challenging aspects of underwater exploration due to unpredictable terrain, high pressure, and limited visibility. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and drones must navigate safely through complex environments, where even minor errors can damage equipment or disrupt sensitive ecosystems.

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have increasingly been applied to enhance autonomous navigation by integrating real-time sensor data from acoustic Doppler devices, inertial measurement units, and pressure gauges (Amazinum, 2023; Jiang & Zhu, 2022). Machine learning models process these inputs to construct high-resolution maps of the surrounding underwater environment, allowing drones to make rapid navigation decisions while adapting to dynamic conditions. Such AI-enabled autonomy significantly improves mission success rates, reduces human intervention, and minimizes operational risks to both personnel and fragile marine ecosystems (Simplilearn, 2023).

The application of AI in seabed resource modeling has introduced a new paradigm in marine geoscience. Machine learning techniques allow researchers to combine multi-modal sensor data to generate accurate three-dimensional reconstructions of the seafloor and predict resource distributions over large spatial scales (Jiang & Zhu, 2022). For instance, Neettiyath et al. (2019) demonstrated the estimation of cobalt-rich manganese crusts (Mn-crusts) on the seafloor using an AUV equipped with sub-bottom sonar and light-profile mapping systems. The sonar provided measurements of crust thickness, while the light-profile system enabled 3D color reconstruction of the seabed. Subsequently, machine learning classifiers segmented the seafloor into categories such as Mn-crusts, sediment, and nodules, allowing researchers to calculate both percentage coverage and mass estimates per unit area along AUV transects.

In addition, De La Houssaye et al. (2019) integrated machine learning and deep learning techniques with traditional geoscientific regression models to predict the O18/O16 isotope ratio as a global proxy for sediment age. Similarly, Ratto et al. (2019) applied generative adversarial networks (GANs) trained on thousands of ray-traced small scenes to rapidly generate large-scale, high-fidelity representations of the ocean floor, achieving minimal processing artifacts. These examples highlight how AI-based models can combine physics-informed and data-driven methods to simulate and reconstruct seabed structures efficiently and accurately (Jiang & Zhu, 2022).

AI-equipped sensors further expand the ability to monitor chemical, physical, and biological ocean parameters. These sensors, deployed on AUVs, buoys, or even marine organisms, can continuously record key metrics such as pH, salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity. Machine learning enables sensors to adapt over time, enhancing their predictive capability and allowing timely responses to environmental changes (Amazinum, 2023; Simplilearn, 2023).

Beyond in-situ measurements, AI has proven instrumental in processing vast satellite datasets for environmental monitoring. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can detect and quantify ocean phenomena such as chlorophyll concentration, sea ice extent, and surface temperature anomalies. Training on extensive satellite image datasets allows these models to assess long-term trends, detect anomalies, and support climate change impact studies on marine ecosystems (Jiang & Zhu, 2022). The integration of satellite imagery with in-situ sensor data creates a multi-scale, multi-source framework for comprehensive ocean observation, resource mapping, and ecosystem management.

In summary, AI has transformed deep-sea resource modeling by enabling autonomous navigation, high-resolution 3D seabed reconstructions, predictive environmental monitoring, and large-scale satellite data processing. The synergy of machine learning, deep learning, and advanced sensor technology provides a robust platform for exploring previously inaccessible ocean regions while safeguarding marine ecosystems and facilitating sustainable resource management (Amazinum, 2023; Jiang & Zhu, 2022; Simplilearn, 2023).

3.3.Recognition of behavioral patterns

Feeding behavior is very important for the health of marine animals and the overall productivity of their ecosystems. AI can help scientists monitor how animals feed by analyzing data from sensors attached to them, such as accelerometers, cameras, or GPS trackers. These sensors collect information about the animal’s movements and surroundings, and AI can process this data to identify behaviors like hunting, eating, or how long and how often they feed (Amazinum, 2023).

For example, in studies of penguins, accelerometers detected sudden movements when the penguins grabbed prey. AI then analyzed these movements to give a detailed picture of the penguins’ feeding schedule, including the timing, duration, and frequency of meals. This information helps researchers understand the availability of food, the quality of the habitat, and how the animals are doing overall (Amazinum, 2023).

AI can also help scientists understand how different marine animals interact with each other and their environment. By combining data from genetics, behavior, and observation, AI can detect patterns in how animals affect each other and how environmental changes impact ecosystems. This helps researchers spot problems early and take steps to protect animals and habitats.

A practical example is coral reefs. Allen’s Coral Atlas uses AI to compare satellite images with pictures taken in the field. This allows scientists to monitor the health of reefs, detect damage or bleaching, and make decisions to protect the ecosystem (Amazinum, 2023).

Using AI to study behavior and interactions gives scientists more accurate and detailed information than traditional observation methods. It allows for continuous monitoring, helps detect problems early, and supports better decisions for conservation. In dynamic marine environments, where observing animals is often difficult, AI makes research faster, easier, and more reliable (Amazinum, 2023).

4. Data to Knowledge

Turning raw ocean data into usable knowledge requires several linked steps: careful data collection, robust preprocessing and annotation, scalable model training and evaluation, and finally integration of model outputs into decision-making. Recent reviews and perspectives in marine science emphasize that artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, can remove major bottlenecks in this pipeline, but doing so requires suitable data infrastructure, clear validation practices, and close collaboration between marine biologists and data scientists (Goodwin et al., 2022; Ditria et al., 2022; Andreas et al., 2022).

Figure 4: Data to wisdom (source: https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/918104/fmars-09-918104-HTML/image_m/fmars-09-918104-g001.jpg)

4.1.From sensors to usable data

Oceans generate many types of raw data: camera and video streams, sonar returns, passive acoustic recordings, environmental sensor logs, and remote-sensing imagery. Each data type has its own preprocessing needs before it can be fed to machine learning systems. Goodwin et al. (2022) underline that image- and audio-based records are increasingly central to non-invasive monitoring because they capture abundance, behaviour, and distribution without heavy field effort. Andreas et al. (2022), writing about bioacoustics and whale communication, also stress that collecting standardized, high-quality acoustic recordings and associated metadata (time, location, sensor orientation, context) is essential for downstream automated analysis.

Key early steps therefore include synchronizing timestamps, calibrating sensors, removing obvious noise, and converting raw files into analysis-ready formats (e.g., spectrograms for sound, rectified frames for imagery). Ditria et al. (2022) emphasise that building pipelines which consistently apply these preprocessing steps so outputs from different assets are comparable is a prerequisite for producing reliable inference with AI.

4.2.Annotation and labels

Supervised learning methods dominate current marine biology AI applications; they require labeled examples. Goodwin et al. (2022) and Ditria et al. (2022) both note that manual annotation (labelling species, drawing bounding boxes, marking call start/stop times) is time consuming and often the main limiting factor in model development. Thus, a central part of the “data to knowledge” chain is creating, curating, and sharing high-quality labelled datasets — and adopting practices (metadata standards, annotation guidelines, versioning) that make labels reusable across projects.

To ease the labelling burden, the literature recommends semi-automated strategies: active learning (where the model selects the most informative samples for a human to label), crowdsourcing with clear quality controls, and using pre-trained models to accelerate initial annotation. Goodwin et al. (2022) show how transfer learning taking a model trained on a large, general dataset and fine-tuning it on a smaller, domain-specific dataset is particularly useful in marine biology, where labelled data are often scarce.

4.3.Training and validation

After annotation, model development follows standard machine-learning practice: split datasets into training, validation and test sets; tune hyperparameters on validation data; and assess final performance on held-out test data. Both Goodwin et al. (2022) and Ditria et al. (2022) stress that transparent reporting of these splits, the metrics used (precision, recall, F1, AUC, confusion matrices), and potential sources of bias is essential for reproducible science.

A recurring caution is domain shift: models trained in one region, sensor setup, or season may underperform when applied elsewhere. Cross-validation, spatially or temporally stratified testing, and explicit domain-adaptation methods are recommended to quantify and mitigate this risk (Goodwin et al., 2022). Ditria et al. (2022) highlight that reporting uncertainty and error bounds and propagating that uncertainty through ecological inferences — is critical whenever model outputs are used for management.

4.4.End-to-end automated workflows and model deployment

Moving from research prototypes to operational systems requires reliable, maintainable pipelines. Goodwin et al. (2022) describe how automated ML pipelines — from ingestion through preprocessing, model inference, and human-in-the-loop verification — allow large, multi-year datasets (images, videos, acoustic archives) to be processed at scale. Ditria et al. (2022) add that cloud platforms, containerized workflows, and standard interfaces for data and metadata are practical enablers of reproducibility and multi-site deployments.

Importantly, the reviews emphasise human oversight: automated suggestions should be verified, edge cases flagged, and model outputs updated as new labelled data arrive. This iterative retraining and monitoring prevents performance degradation as environmental conditions change.

4.5.Specialized data types: acoustics and behavior

Acoustic data pose distinct challenges — long continuous recordings, high data volumes, and complex signal structures. Andreas et al. (2022) outline a roadmap for large-scale bioacoustic analysis aimed at decoding sperm-whale communication. Their recommendations apply more generally: collect high-quality, synchronized recordings; build unit-detection tools (to find the basic sound elements); assemble hierarchical representations (from units to phrases to higher-order structure); and validate models through behavioral context or interactive experiments. Aggregating acoustic, positional and behavioral metadata enables construction of longitudinal, individual-level datasets — “social networks” of animals — that are powerful inputs for subsequent machine-learning analyses (Andreas et al., 2022).

4.6.From prediction to explanation: hybrid approaches

Purely data-driven models (data-driven modelling, DDM) can reveal patterns and make accurate short-term predictions, but they may not explain mechanistic processes. Both Goodwin et al. (2022) and Ditria et al. (2022) argue for hybrid workflows that combine mechanistic (process-based) models with ML-based pattern discovery. Such hybrids can leverage the predictive power of ML while retaining interpretability and links to known ecological processes. This helps managers trust output and make actionable decisions.

5. Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is reshaping how marine ecosystems are observed, analyzed, and protected by transforming data-rich but traditionally slow research processes into scalable, automated systems. Across ecological monitoring, bioacoustic tracking, and image-based species detection, AI provides the capacity to process vast and complex datasets at speeds and accuracies that far exceed human-driven methods. Deep learning has already demonstrated its ability to overcome long-standing analytical bottlenecks by rapidly classifying species, detecting ecological patterns, and extracting meaningful information from imagery, video, and acoustic recordings—tasks that previously required weeks or months of manual work (Goodwin et al., 2022). At the same time, automated monitoring platforms and integrated sensing systems now generate continuous streams of ecological, behavioural, and environmental data that can be synchronized and transformed into new insights about animal movements, habitat use, and long-term ecosystem change (ScienceDirect article).

These advances are not merely technical achievements; they meaningfully expand the scope and resolution of conservation science. AI-enabled workflows offer near real-time detection of ecosystem changes, greater consistency than manual processing, and the ability to scale monitoring across larger spatial and temporal ranges than ever before. As Ditria et al. (2022) emphasize, integrating AI into conservation practice has the potential to provide managers with timely, data-driven evidence needed to respond effectively to environmental pressures and to evaluate the success of restoration efforts. However, challenges remain—particularly the need for larger, well-annotated datasets, improved model transparency, and a clearer understanding of how errors and biases influence ecological inference.

Overall, AI should not be seen as a replacement for marine biology reasearch but as a powerful extension of it. By combining automated data processing, machine learning, and domain knowledge, researchers can transition from data scarcity and manual bottlenecks to continuous, high-resolution understanding of marine systems. As computational capabilities grow and interdisciplinary collaboration strengthens, AI will play an increasingly central role in developing predictive, responsive, and evidence-based conservation strategies—ultimately supporting more resilient marine ecosystems in a rapidly changing world.

References

Dogan, G., Vaidya, D., Bromhal, M., & Banday, N. (2024). Artificial intelligence in marine biology. In A Biologist’s Guide to Artificial Intelligence (pp. 241–254). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978‑0‑443‑24001‑0.00014‑2

Ditria, E. M., Buelow, C. A., Gonzalez‑Rivero, M., & Connolly, R. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence and automated monitoring for assisting conservation of marine ecosystems: A perspective. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, Article 918104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.918104

Goodwin, M., Halvorsen, K. T., Jiao, L., Knausgård, K. M., Martin, A. H., Moyano, M., Oomen, R. A., Rasmussen, J. H., Sørdalen, T. K., & Thorbjørnsen, S. H. (2022). Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: Overview, applications, and outlook. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255

The Ocean Cleanup. (2021). Quantifying floating plastic debris at sea using vessel‑based optical data and artificial intelligence. Remote Sensing, 13(17), 3401. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13173401

Andreas, J., Beguš, G., Bronstein, M. M., Diamant, R., Delaney, D., Gero, S., Goldwasser, S., Gruber, D. F., de Haas, S., Malkin, P., Pavlov, N., Payne, R., Petri, G., Rus, D., Sharma, P., Tchernov, D., Tønnesen, P., Torralba, A., Vogt, D., & Wood, R. J. (2022). Toward understanding the communication in sperm whales. iScience, 25(6), Article 104393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104393

Amazinum (2023). Deep dive: AI’s impact on marine ecology. Amazinum. https://amazinum.com/insights/deep-dive-ais-impact-on-marine-ecology/

Innovation News Network (2022). The use of artificial intelligence in marine biology research. Innovation News Network. https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/the-use-of-artificial-intelligence-in-marine-biology-research/17247/

Cleaner Seas (2025). From coral reefs to code: Training AI to recognise marine species and ecosystems – Part 1. Cleaner Seas. https://cleanerseas.com/from-coral-reefs-to-code-training-ai-to-recognise-marine-species-and-ecosystems/

Cleaner Seas (2025). From coral reefs to code: Training AI to recognise marine species and ecosystems – Part 2. Cleaner Seas. https://cleanerseas.com/from-coral-reefs-to-code-training-ai-to-recognise-marine-species-and-ecosystems/

Simplilearn (2023). Applying AI in marine biology and ecology. Simplilearn. https://www.simplilearn.com/applying-ai-in-marine-biology-and-ecology-article

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. (2022). Unlocking the power of AI for ocean exploration. MBARI Annual Report 2022. https://annualreport.mbari.org/2022/story/unlocking-the-power-of-ai-for-ocean-exploration

National Centers for Environmental Information [NCEI] (2018). Mapping our planet, one ocean at a time. NOAA. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/mapping-our-planet-one-ocean-time

Jiang, M., & Zhu, Z. (2022). The role of artificial intelligence algorithms in marine scientific research. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, Article 920994. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.920994

FruitPunch AI. (2023). Understanding seals with AI. FruitPunch AI. https://www.fruitpunch.ai/blog/understanding-seals-with-ai

Wageningen University. (2023). Researchers develop AI model that uses satellite images to detect plastic in oceans. Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2023-11-ai-satellite-images-plastic-oceans.html