Introductions

The digital environment has been rapidly changing over the past years. People’s interaction with services, products, and information has dramatically transformed. With the growth of social media, e-commerce, and online services, companies have learned to improve user experiences, making them more intuitive and engaging to maximize customer satisfaction and optimize profit. Although many of these designs aim to be ethical and user-friendly, concerns are rising about more manipulative designs known as dark patterns.

Deceptive patterns refer to manipulative techniques in user interface designs that deliberately deceive users into making decisions that benefit the company, often at the client’s expense. Unlike more traditional designs, which prioritize clarity and ease of use, dark patterns rely on psychological manipulation to navigate users toward choices that may be hidden, misleading, or in conflict with their best interests.

These manipulative tactics are common in various online interactions, including signing up for services, navigating e-commerce sites, and canceling subscriptions. As digital experiences become more omnipresent and personalized, the topic of dark patterns has raised major legal and ethical concerns. How can we create a future where technology enhances lives without undermining trust?

Psychological Foundations Behind Dark Patterns

In most cases, the behavior of a person can be seen as an outcome of made decisions. By understanding these decision-making processes, it’s possible to predict people’s behavior. Moreover, digital experiences can be designed to support or influence such behavior.

One of the factors that can influence decision-making is people’s mood, which can be affected by numerous things. It also determines if a decision is based on emotions or logical reasons. A good example of this is the influence of mood through color, which can affect behavior in various ways. For instance, red buttons usually evoke danger or urgency which leads to impulsive actions. On the contrary, green checkmarks can signal safety and reassurance, subtly pushing users toward one specific option.

Dark patterns also play on incidental emotions – emotions that cannot be controlled, such as frustration or relief, to prompt specific actions. One way through which designs take advantage of people’s emotions is through nudging. The concept of nudges is based on choice architectures that predictably influence user’s decisions without restricting their freedom of choice. This effective tool has been successfully applied in numerous areas, such as education, health, and finance. Examples include putting healthy food at eye level or near the checkout counters in schools or supermarkets or setting default options for organ donations.

Furthermore, companies optimize these deceptive designs using A/B testing (also known as split testing), a user experience research method. A/B testing compares two variants of digital content to determine which version performs better based on the user’s behavior. In this method, users are randomly divided into two groups. Every group interacts with different versions. Key performance indicators, like time spent on the page, click-through rates, or average revenue per user, are measured and analyzed to identify which variant is more effective.

Another advanced testing method that businesses use is multivariate testing which evaluates multiple variables simultaneously in a single experiment. This testing provides a deeper understanding of each variable’s impact and can uncover insights that might not emerge from single-variable tests, while also saving time (Maier & Harr, 2020).

Cognitive biases

Two important factors that are influential in the decision-making process are heuristics and biases. Heuretics are simple and efficient rules that people use to make decisions and solve problems. These cognitive functions simplify complex processes by focusing on key pieces of information rather than processing every detail. The rules have been shown to work well in most situations, but in certain cases, they can result in cognitive biases – systematic patterns of deviation from rationality in judgment. In design, heuristics can be used to guide users towards better decisions or it can be used to exploit biases through deceptive tactics (Azzopardi, 2021).

Among the commonly studied cognitive biases in the context of dark patterns are:

Anchoring bias

Users tend to rely too heavily on the first piece of information presented (the “anchor”) when evaluating their choices. For example, displaying a high price first, followed by a discounted price, can make the latter seem like a better deal than it is.

Confirmation bias

Tendency to interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting opinion and beliefs, while disregarding information that contradicts the initial opinion. Individuals selectively search for evidence that aligns with their current beliefs, making it hard for them to change their mindset. For instance, companies may use highly positive reviews of customers to manipulate potential buyers.

Status quo bias

Tendency to favor the current situation over an alternative, to avoid risk and potential loss. Decision-makers have a higher probability of choosing a default option (status quo). This bias has been shown to affect multiple important economic decisions. For example, in subscription services, users often stick with automatic renewals due to a default option.

Social proof

Psychological phenomenon where individuals tend to follow the actions of others. It is more applied in situations where people are uncertain how to behave. This mental shortcut is often used in design and marketing, where testimonials, ratings, or “most popular” labels are used to influence buyers’ actions. For instance, the number of people who have purchased the product can make users follow the crowd and make an impulsive decision.

The reciprocity principle

This concept describes the human tendency to feel obligated to return favors and gestures. It’s deeply rooted in human social behavior. A typical example of this principle is offering a free sample or gift. Companies are expecting that customers might sign up for a service, agree to additional terms, or make a purchase out of indebtedness.

Loss aversion

People are more motivated to avoid losses than to gain something of the same value. Meaning that the emotional impact of losing something is usually much stronger than the satisfaction of gaining the equivalent. In decision-making, people often make choices that avoid risks and losses, even if they are irrational and unbeneficial. For instance, offers like “Don’t miss out on this deal!” increase urgency and pressure buyers to take quick action.

Scarcity

This principle is based on the idea that people tend to place a bigger value on things that seem to be in limited supply. When something is scarce it usually motivates individuals to act quickly and acquire it before it’s gone. It is frequently used in sales, where products are labeled as limited.

Dark patterns manipulate decision-making processes in ways that undermine users’ autonomy by leveraging cognitive biases and strategic designs. These deceptive techniques take advantage of psychological tendencies, usually without users’ awareness, and financially benefit companies or platform owners. Understanding these úsychological foundations is crucial for recognizing how dark patterns work and how they impact people’s behavior.

Types of dark patterns

Dark patterns can manifest in various forms, ranging from subtle psychological manipulations to outright deceptions that leave users with feelings of manipulation or even betrayal. The term was first mentioned by user experience designer Harry Brignull in 2010 to describe manipulative design strategies that exploit cognitive biases for financial gain.

Below are some of the most common types of dark patterns and their examples found in digital interfaces:

- Bait and Switch

A tactic that occurs when users intend to perform a specific action but are redirected or forced into another one. This can often be seen on websites. By clicking on a button or a link the user is expecting to be led to a predictable outcome, but instead, they are led to an entirely different page. For example, advertising of a free or greatly discounted product that is currently unavailable. After announcing that, the page offers similar products of much higher and lesser quality. - Roach Motel

This dark pattern is typical for its straightforward way to get in but a very difficult path to get out. Roach Motel is named for its similarity to a roach trap. It’s common among platforms that use subscription-based models. Examples include websites where users may quickly sign up for a free trial. But when attempting to cancel, they face an intentionally hard and confusing process that discourages them. They might need to print and mail their cancellation request or phone with absurd waiting times. Many clients therefore end up paying additional charges. - Confirmshaming

This technique works by triggering uncomfortable emotions, such as shame or guilt, to pressure users into taking a certain action. Apps or websites that use this dark pattern usually label opt-out buttons with derogatory language, aiming to make users feel bad or uncomfortable about declining the offered feature or service. By purposely taking this approach, confirm-shaming is trying to increase the likelihood that users will give up their desired action, ultimately benefiting the companies.

In 2018 an e-commerce website selling medical supplies used this specific deceptive pattern. When requesting permission to send notifications, the website presented an opt-out choice as “No, I prefer to bleed to death”. This option was targeted to customers who probably were already exposed to the trauma of accidents, leaving them with uncomfortable feelings. - Hidden Costs

Hidden Costs involves adding additional fees or charges long after the user has made their initial decision. This tactic is used in e-commerce, where the price of a product only is usually very low. After investing time and effort into the transaction, hidden costs such as shipping, service charges, or taxes are shown. By that point, users are more likely to proceed with the purchase. - Pre-selected Options

Preselection works with the default effect of cognitive bias – people tend to go with the option that is already pre-chosen for them, even if there are other available choices. Most providers are aware of this phenomenon and often exploit it to take advantage of consumers. The most common tactic is to display a pre-ticked checkbox. Other approaches include pre-selecting options during a multi-step process or automatically putting items in the customer’s cart. These selections are usually hidden and very difficult to spot, making it easy for users to overlook them. - Forced Continuity

This deceptive pattern occurs when users are enticed with a limited-time promotional offer or a free trial, only to have their subscription automatically renewed once the trial period ends. Often, the renewal process is not clearly explained, leaving users unaware that they will be charged after the end of the trial. This lack of transparency may lead to unexpected expenses, as clients unknowingly authorize the continuation of the service. The difficulty of the cancellation process is often used to increase the chances that users will either forget to cancel or become discouraged from doing so. - Trick Wording

The trick wording pattern involves using misleading and ambiguous language to deceive and take advantage of prompt users. Most people don’t read and dwell on every word. They rather scan-read through the volume of information they are faced with. This dark pattern exploits the scan reading strategy, presenting content that appears to be saying one thing when it actually tells something entirely different that is not in the user’s best interest. - Privacy Zuckering

Privacy Zuckering is a dark pattern named after Facebook co-founder and Meta Platforms CEO Mark Zuckerberg. This practice tricks users into sharing more personal information than they intended to. It employs deceptive interfaces and misleading language to make users agree to intrusive privacy settings, often without realizing the extent of the shared data. For example, users could connect their social media accounts or sync their contacts and unknowingly offer their data for marketing purposes or share them with third parties. Privacy Zuckering has been observed in many platforms that prioritize data collection for profit. - Disguised Ads

This deceptive pattern works by intentionally blurring the line between advertisements and genuine content, creating confusion for users. The ads are usually designed to resemble interface elements, related articles, posts, or other relevant content that users will more likely interact with. Disguised ads boost ad impressions for website owners and help advertisers achieve higher clickthrough rates, potentially resulting in more sales. This deceptive approach takes strategic advantage of users’ expectations and trust in the platform’s designs. - Price Comparison Prevention

When making a purchase decision, users will often try to weigh up the price with the features and their personal needs. This process usually involves comparing multiple products before making a final decision. If this evaluation becomes too challenging, users may feel overwhelmed, leading them to make impulsive decisions. The price comparison prevention pattern exploits this by complicating the evaluation process, such as hiding the key details or presenting inconsistent information. This enables the provider to steer users toward a decision that generates more profit, but may not be in the user’s best interest.

Ethical and Legal Implications of Dark Pattern Design

Digital technology is increasingly becoming part of our lives. With that it brings more opportunities but also challenges in how design can influence users. While most businesses employ ethical design, the use of dark patterns is becoming more common. These deceptive patterns are raising significant concerns, as they undermine users’ autonomy. Their information is often collected and sold by organizations without user’s permission. As awareness of manipulative practices grows, so does the call for more ethical designs in the digital landscape.

Ethical implications

A key ethical dilemma emerges when designers face the choice of using persuasive techniques to lead users toward decisions that rather benefit the business or prioritizing user needs and preferences. The ethical concerns surrounding dark patterns primarily revolve around the respect for user autonomy. Employment of deceptive patterns violate the user’s ability to make free and informed decisions.

On the other hand, ethical designs prioritizes user well-being and transparency. These designs provide clear and easy to understand options which allows them to make free choices. Several frameworks have come up to guide designers how to conduct and determine features of products and how to assess their moral worth. These designs can help reinforce positive behavior and prevent negative consequences.

Ethical design principles revolve around human experience, effort and rights. This illustrates a framework called “Ethical Hierarchy of Needs” created by Aral Balkan and Laura Kalbag. It shows how each layer of the pyramid is dependent on the layer beneath to ensure that design is ethical.

Ethical design principles provide a concrete framework through which to create products that take into consideration social responsibility and user well-being. These principles help guide developers toward building ethical, user-friendly, and sustainable products:

- Usability: Design products that are easy to use, ensuring that they are intuitive, efficient, and satisfying for users. Focusing on improving the learning process, minimizing errors, and ensuring that users can navigate and remember how to use the product with ease.

- Accessibility: Availability of products for everyone, that includes accommodating visual, auditory, motor impairments, and supporting assistive technologies that help users interact with digital content.

- Privacy: Privacy is the core of ethical design. It is about taking proactive measures to protect the user’s data through encryption, for example, and placing full control over personal data in the hands of the users themselves.

- Persuasion: Integrate transparency into design to enable users to make informed decisions. Users must be able to understand what they are agreeing to and how their actions or choices will affect them.

- Focus: Distractions are everywhere in today’s digital world. Designers should reduce unnecessary interruptions, minimize addictive features, and create calm, focused user experiences that enhance productivity rather than distract users.

- User Involvement: Engage users early and consistently throughout the design process to truly understand their needs. Continuous feedback and collaboration with users ensure that the final product is helpful to them and meets their needs.

- Sustainability & Society: Ethical design is more than just individual products; it covers broader social responsibility. Designers should consider the footprint their work leaves on the environment, climate change, and social inequality, and their products should contribute to sustainable and equitable practices (Overkamp, 2019).

Despite the effort of applying ethical design, there is still a gap in the application of these rules in real-world design. This is often due to organizational pressures, a profit-driven environment, and the lack of effective tools in design practice.

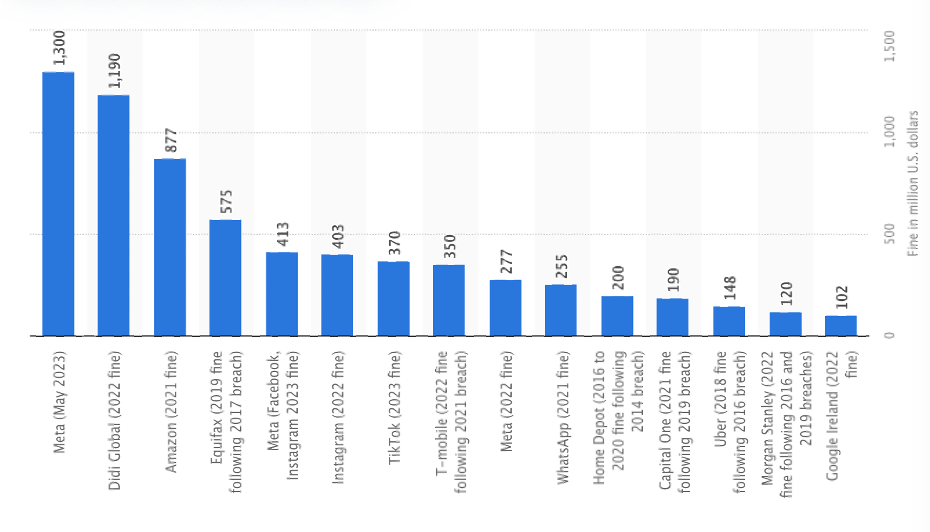

Legal implications

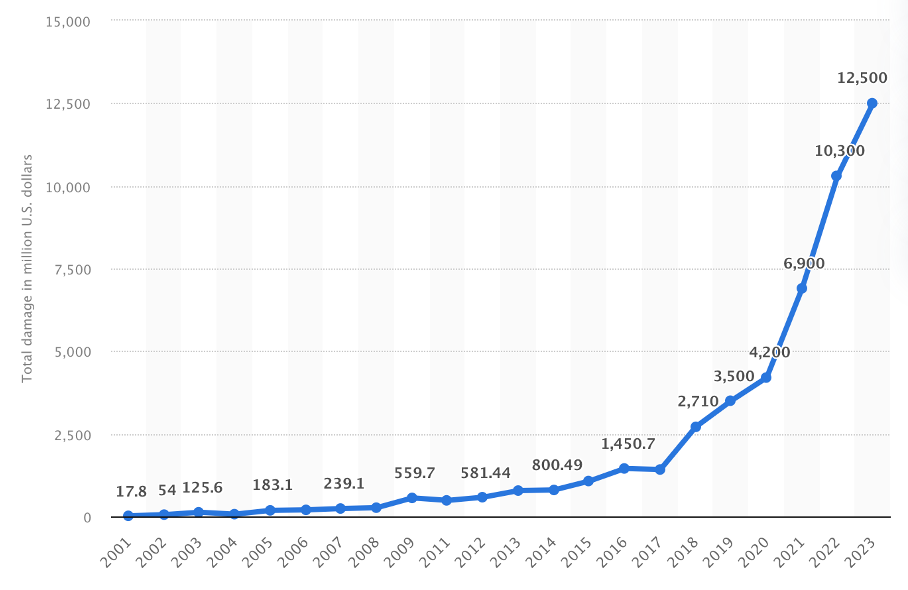

As the occurrence of dark patterns continues to rise, so does the regulation from lawmakers and regulators. Various legal frameworks have been developed to address deceptive techniques in the digital environment. These efforts intend to protect consumers from exploitation and ensure that businesses are accountable for manipulative design tactics.

GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation)

One of the most significant regulatory frameworks in recent years is the General Data Protection Regulation. This regulation was implemented in 2018 by the European Union . While the GDPR primarily focuses on data protection, it also addresses issues related to user’s rights and their ability to control their given consents to the digital services.

The GDPR forces organizations to ask for user consent before any data is collected, to provide clear information about how the data will be processed and to give users opportunity to allow or refuse the collection. Moreover, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity can not be interpreted as implied consent and the request must be clearly distinguishable from other interface elements. However, regulations only apply to the use of consents, not to dark patterns, which includes many more aspects.

FTC (The Federal Trade Commision) and the Regulation in the USA

In the United States, the regulation of advertising practices and protection of consumer rights is the responsibility of the Federal Trade Commission. While the FTC is not yet able to effectively address problems of dark patterns, it has issued some guidelines and has investigated companies that use manipulative practices. However, the majority argue that current regulations in the USA are insufficient.

Challenges in Regulation

One of the main issues in regulating deceptive patterns is the constant evolution of digital design. New practices emerge regularly, and companies are able to quickly adapt to them and, therefore, avoid detection. Furthermore, regulations that may apply to one country or continent might not have a significant impact on companies that operate internationally in many countries.

Moreover, defining what exactly dark patterns mean is a very complex process. While some designs are obviously manipulative and deceptive, some others may not be that apparent. Government institutions and regulations need to find a balance between allowing businesses to compete with each other and also protecting consumers. Possibly in the future, we may see clearer definitions of dark patterns, more enforcement actions, and higher fines for companies engaging in these manipulative techniques.

Impact of Dark Patterns on Users

The impact of dark patterns is significant, and as a result, there are immediate and long-term negative consequences for users, which affect them financially, emotionally, and psychologically. By exploiting psychological manipulation, these practices often leave users feeling misled, annoyed, and even regretful of the choices they have made, thus losing trust in the digital platforms they use. Most common consequences include:

Financial Consequence

Dark patterns often result in direct financial losses for users. These manipulative methods are very often hidden in additional costs, subscriptions to services that are not wanted, and long-term financial commitments that users were not fully aware of.

Examples include “free trials,” which are easy to sign up for but then hard to cancel; users who think they are canceling find themselves charged for many months or years after the trial has technically expired. These surprise charges cause financial hardship and much frustration. Similarly, the practice of hidden fees at checkout on e-commerce sites is a ploy to make something seem more affordable than it really is. People may think that they got a good deal until later they realize that their total costs are much higher than what was initially anticipated.

Emotional and Psychological Effects

The emotional impact of dark patterns is significant. Victims of these manipulative designs frequently experience frustration, embarrassment, and anger. The realization that one has been tricked can undermine confidence in their ability to navigate online services. Over time, this sense of manipulation can result in a broad, negative impact on the user’s relationship with digital platforms, often making them more wary of online interactions.

Loss of Trust

Perhaps the most significant long-term impact of dark patterns is the loss of trust. Once users realize they’ve been manipulated by deceptive practices, they are less likely to return to the platform or service in the future. This loss of trust can have a negative effect, damaging the company’s reputation and decreasing customer loyalty.

In the age of online reviews and social media, bad experiences with dark patterns can spread quickly, leading to public backlash and negative press. Unhappy customers will more than likely share their experiences and tell others to avoid platforms that try to manipulate them with such designs. Not only does this affect their reputation, but it might also lead to a drastic fall in customer loyalty and, as a result, profits. In an environment where trust is paramount, the damage caused by dark patterns can be difficult to repair, even with improved customer service.

Privacy Concerns

Dark patterns are also closely tied to privacy violations. Many dark patterns involve pushing users into making choices that compromise their data or privacy, such as opting into unnecessary data collection or agreeing to share personal information without fully understanding the consequences.

For instance, a social media platform might use a pre-selected checkbox to automatically enroll users in data-sharing practices that benefit the company, without fully informing them of how their data will be used or stored. This lack of transparency may result in serious breaches of privacy, especially when it involves sensitive data like medical, financial, or personal information. Over time, this will erode users’ confidence in the security of their information, contributing to a growing mistrust of online platforms and their practices (Naceur, 2023)

The Future of Dark Patterns

As the digital environment continues to rapidly evolve, the dark patterns will likely adapt in response to new technologies and consumer behaviors. The development of artificial intelligence and machine learning may open new opportunities to manipulate users at an even deeper level, possibly through more personalized manipulative techniques that will be harder to detect.

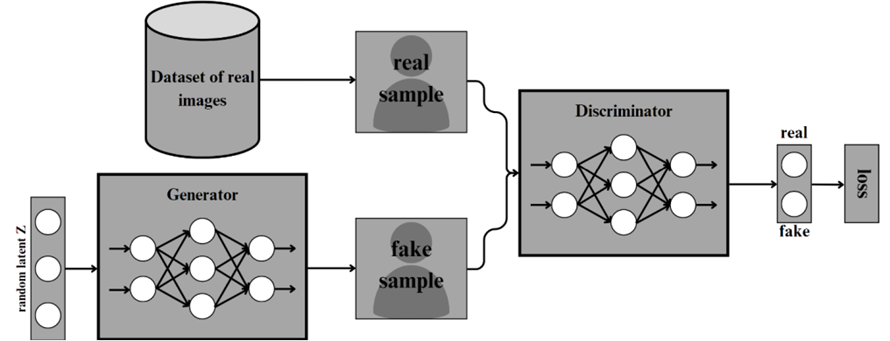

AI- driven dark patterns

The integration of generative artificial intelligence into digital design increases the complexity of dark patterns. AI enables businesses to analyze each user’s behavior at a deep level, crafting personal-targeted manipulative practices and advertisements that will exploit individuals’ vulnerabilities.

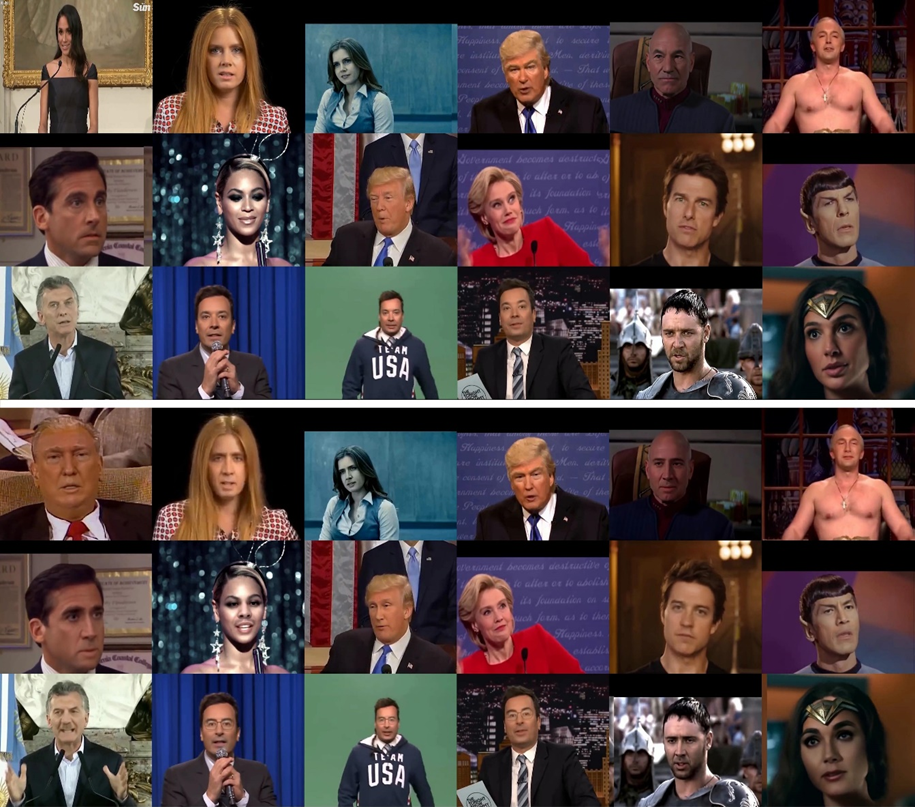

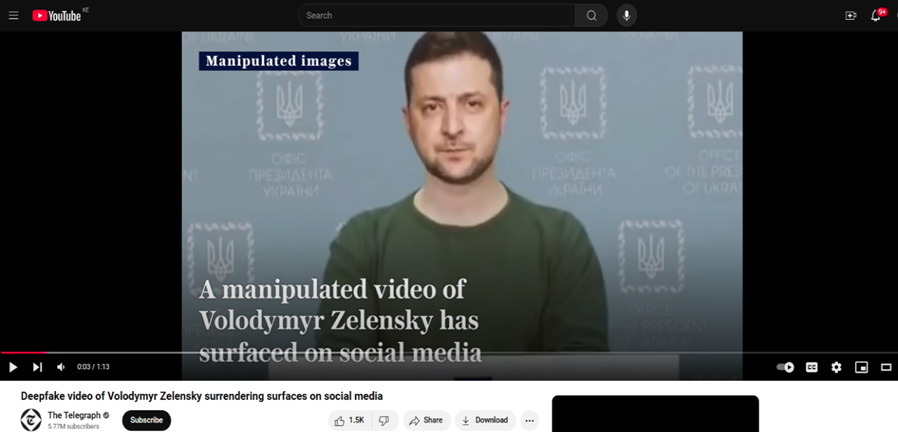

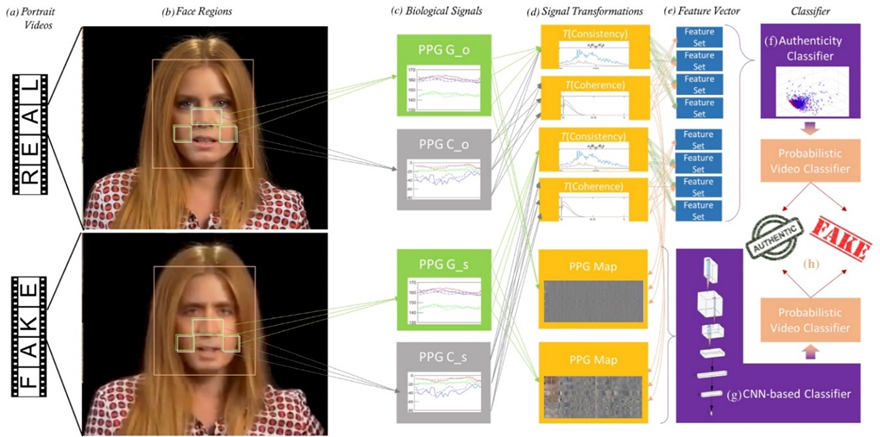

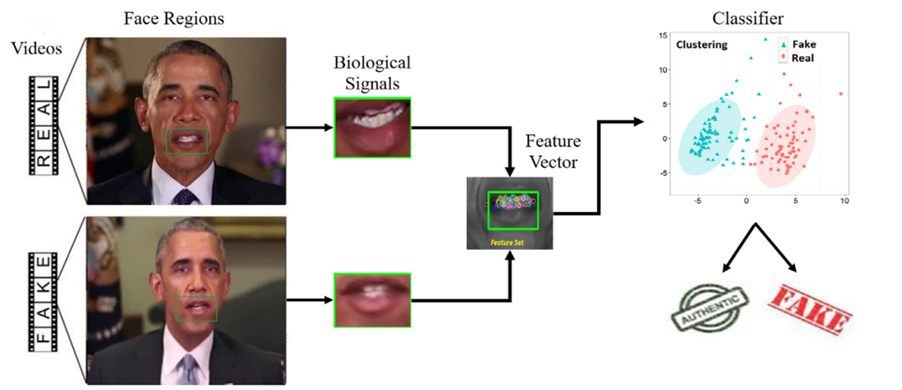

For instance, AI could generate believable deep fakes that will simulate trusted individuals to deceive users into sharing their personal information. By mimicking the voice, appearance and gestures of someone trusted, these interactions could become highly convincing. Another example could be assessing a user’s emotional state and serving fabricated content to take advantage of these emotions. This could push users towards more impulsive decisions that would favor companies profits.

Challenges in Detection

As dark patterns evolve through AI, detection becomes significantly more difficult. Ability to generate complex and manipulative designs creates a challenge for users, regulators and even developers to recognize unethical techniques. The lack of transparency in AI-generated outputs complicates their accountability (Moloney, 2024).

Ideas how to fight against Dark Patterns

The solution to dark patterns requires a complex approach: user empowerment, industry accountability, and innovative regulatory frameworks. First and foremost is user education in the fight against manipulative tactics in design. Public awareness campaigns can help people to recognize existing dark patterns, enabling them to make better choices online.

While organizations have begun to develop a catalogue of these tactics, broader and more accessible campaigns are needed to reach a wider audience. In collaboration with schools, technology companies, and nonprofit organizations, the information could be passed on to the younger population. Besides that, browser extensions and other tools which could detect and flag dark patterns in real-time can immediately help users. These tools could detect and warn users about manipulative designs, and allow users to make more active choices.

Equally important will be promoting accountability within the industry itself. Companies need to adopt ethical design principles that put user well-being first. This can be achieved by introducing frameworks for ethical design, which guides organizations in prioritizing user autonomy, privacy, and transparency. Businesses should also embrace an approach, where they provide clear and upfront disclosures about their data practices, subscription terms, and fees. Every business can systematically audit interfaces for dark patterns with internal and independent reviewers. Ongoing user feedback is crucial to ensure continued fairness, usability, and lack of manipulation in the products.

On the regulatory front, governments have to evolve existing laws to catch up with the dark patterns. Laws such as the GDPR and the EU’s AI Act have gone some way toward safeguarding users’ data, but they could go further by embedding more specific provisions that deal with these design tactics. For instance, regulations can require companies to provide accessible and straightforward mechanisms for cancellation of subscriptions. Further, there should be global collaboration among regulatory organizations to define what exactly is a dark pattern. This would prevent firms from exploiting jurisdictional gaps, making it harder for them to dodge accountability.

Looking ahead, technology could be used as a key part in the fight against dark patterns. AI systems could be designed to advocate for users by detecting and blocking manipulative practices before they can have an impact. Blockchain technology could also provide a role in the form of verifiable logs of user interactions, making it easier to hold companies accountable for failing to be transparent with their users. Integration of digital literacy programs into education systems could prepare the next generation to critically engage with online platforms and recognize dark patterns as they emerge. By fostering a culture of informed digital citizens, society could reduce the effectiveness of these manipulative practices and ultimately create a more ethical digital landscape.

Conclusions

Dark patterns represent a serious ethical challenge in the digital landscape. While they may provide financial gains for companies, they ultimately damage consumer trust and autonomy in the digital environment. By embracing ethical design practices, businesses can create experiences that prioritize user needs, respect their independence and build long-term relationships based on transparency.

As consumers are becoming more and more aware of these manipulative practices, the pressure on companies to adopt ethical design standards will only be increasing. The future of digital designs is in securing that both businesses and their consumers can thrive in the digital age

List of references

Maier, M., & Harr, R. (2020). Dark design patterns: An end-user perspective. Human Technology, 16(2), 170–199. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/dark-design-patterns-end-user-perspective/docview/2681456628/se-2

Luguri, J., & Strahilevitz, L. (2021). Shining a Light on Dark Patterns. Journal of Legal Analysis, 13(1), 43–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laaa006

Waldman, AE. (2020). Cognitive biases, dark patterns, and the ‘privacy paradox’. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.025

Kollmer, T., & Eckhardt, A. (2023). Dark Patterns. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 65(2), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-022-00783-7

European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

Moloney, M. (2024, June 28). AI driven dark patterns: What does the future hold? Irish Computer Society. https://ics.ie/2024/06/28/ai-driven-dark-patterns-what-does-the-future-hold/

Beta-i. (2023, March 8). Ethical design: What is it and why is it important for you?. https://beta-i.com/blog/ethical-design-what-is-and-why-is-important-for-you

Overkamp, L. (2019, May 30). Daily ethical design. A List Apart. https://alistapart.com/article/daily-ethical-design/

Mathur, A., Mayer, J., & Kshirsagar, M. (2021). What Makes a Dark Pattern… Dark?. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2101.04843

Deceptive Design. (2023). Types of dark patterns. https://www.deceptive.design/types