Introduction

Deepfake technology employs advanced machine learning capabilities to generate verisimilar videos, images, or audio of people. This artificial intelligence (AI) innovation raises questions about truth and lies in ways that make it contentious (Albahar and Almalk, 2019). Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) is a complicated machine learning framework that powers Deepfake. It has two components: The generator and the discriminator. The generator creates false content, while the discriminator verifies its validity against genuine data (Mirsky and Lee, 2021). A big collection of real-life photos, videos, or audio recordings of the subject is used to train the model. This helps the computer recognize facial emotions, vocal intonations, and subtle mannerisms. Finally, it creates a lifelike but pretentious image that can trick even the most skilled viewer.

Principally, deepfake technology is popular because it has the capability to generate photo- or video-realistic results from a given dataset. GANs have facilitated the creation of deepfakes because its source code is open access and is easily available in platforms such as GitHub (Broklyn et al., 2024). As a result, the entry threshold is lower, enabling more people to exploit it for malicious interests. These forms of media are harmful to political systems and journalism as they erode people’s trust (Twomey et al., 2023). The major concern about the proliferation of deepfakes relates to its ability to deceive because it constitutes misinformation and disinformation. Once these deceitful media are generated, users usually share them on social media platforms, where people consume them as unedited content. Most of the audience on these social media platforms inadvertently share deepfakes (Ahmed, 2020).

The implications of deepfakes for cybersecurity are diverse, considering their many applications. For example, deepfake technology can be used to steal identity, whereby malicious persons create convincing content that impersonates others or commits fraud (Broklyn et al., 2024). Cybercriminals exploit this technology to steal other people’s identities, commit financial fraud, and spread misinformation that undermines trust in digital communications and media. These capabilities underline the effect of deepfakes on businesses and individuals, as well as necessitate the creation of new creative channels that can disenfranchise individuals and corporations by compromising the truth (Mustak et al., 2023). The use of deepfake technology raises concerns about the most appropriate strategies that can be used to detect and mitigate its negative consequences. Therefore, this paper examines how deepfake technology has evolved to become a major setback to cybersecurity across the globe and is sustained by misinformation and social engineering.

This paper has six chapters. The first chapter examines how GANs are used to develop deepfakes, and the second chapter discusses the various consequences of deepfakes in cybersecurity, highlighting identity theft, business fraud, and the spread of disinformation. To strengthen the approach in the paper, a review of real-world case studies involving the deepfake, focusing on political manipulation and CEO fraud, is presented in the third chapter. The fourth chapter examines the different methods for detecting deepfakes. Strategies for mitigating the consequences of deepfakes, as well as ethical issues and global perspectives of deepfakes, are presented in chapters five and six, respectively. The paper concludes with an overview of the main insights from the paper and actionable recommendations to suppress the effects of deepfakes in society.

GANS and deepfake technology

Understanding deepfakes

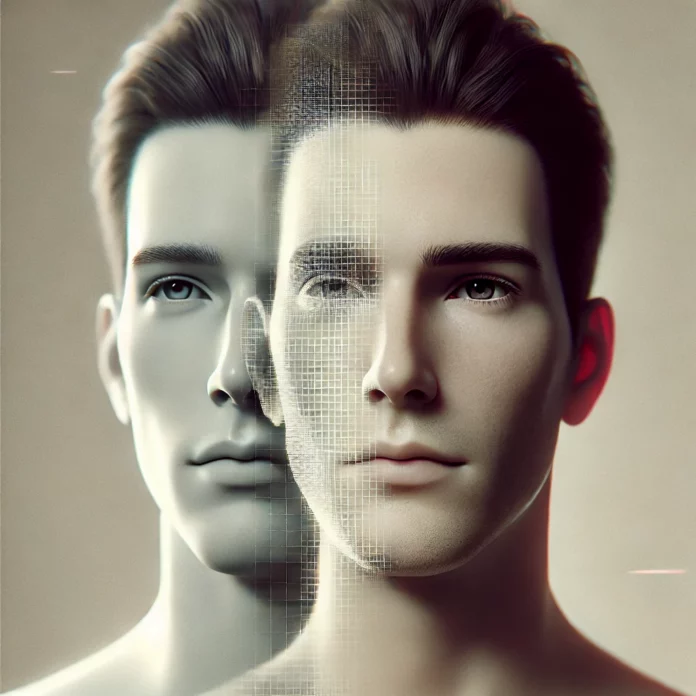

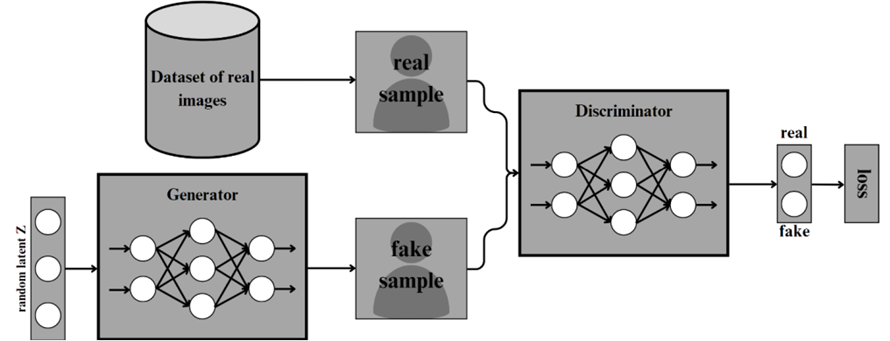

Deepfake technology uses GANs to develop video, audio, and images through an elaborate process involving a generator and the discriminator (Albahar and Almalk, 2019; Mirsky and Lee, 2021). GANs is an approach to generative modeling that uses deep learning methods such as convolutional neural networks. They are unsupervised machine learning models that automatically discover and learn regularities or patterns in input data. This capability makes GANs useful in generating output from the original dataset. Deepfakes use GANs that operate on a continuous feedback loop with the discriminator and generator. Usually, the discriminator and generator neural networks execute opposite functions: the generator accurately mimics real data to make fake images, videos, and sounds while the discriminator determines if the results are real or contrived (Albahar and Almalk, 2019). As the two networks become antagonistic, the generator becomes better at creating convincing false media as the discriminator finds errors and fixes them, making the generator even better at refining its output. Over time, the model learns to replicate the characteristics of the target, including their voice inflections, facial expressions, and behavioral traits (Broklyn et al., 2024). This process creates a synthetic media that is difficult to identify as fake as shown in Figure 1 below. The generator creates images that are realistic beyond the capability of the discriminator to determine if they are fake. Continued training usually culminates in the creation of high-quality fakes.

Figure 1: Generation of Deepfake using GANs. The flow chart is adapted from Yu et al. (2024)

How GANs create deepfakes

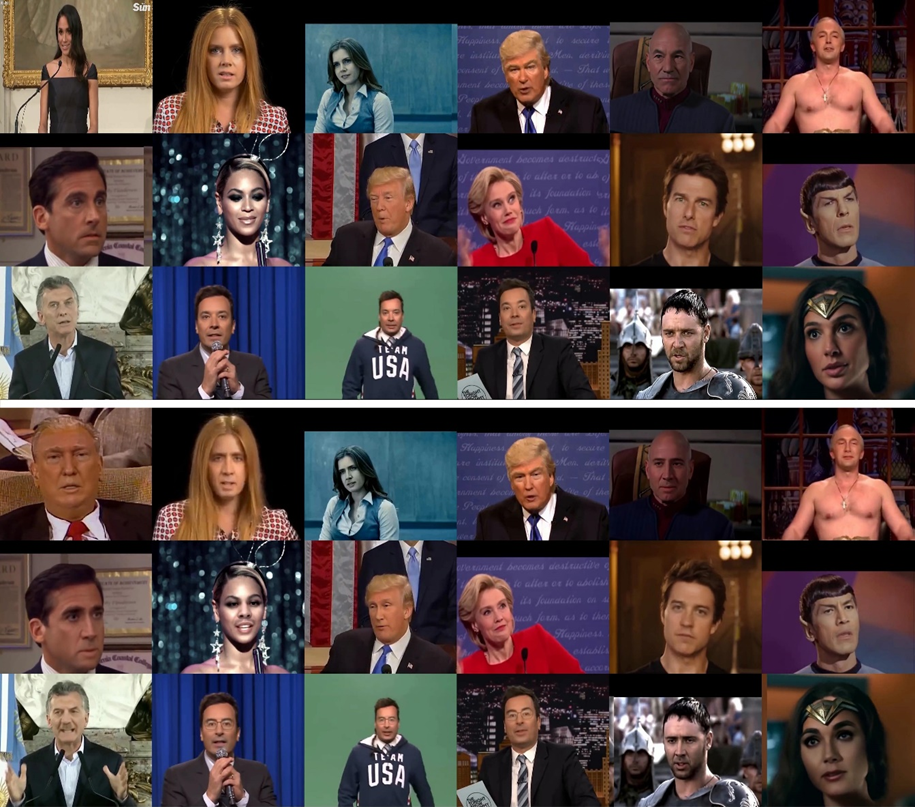

Creating a deepfake starts with collecting large datasets because it involves complex machine learning models. The dataset may contain high-quality pictures, videos, or audio recordings of the target subject based on the user’s desired outcome (Albahar and Almalk, 2019). To create a deepfake video, the user creates a model with thousands of frames of the target’s facial expressions, gestures, and audio samples of their vocal patterns, intonations, and speech (Mustak et al., 2023). The generator of the GAN recreates these aspects as it studies this massive dataset, creating a synthetic person that looks real. Face mapping and replacement are some of the aspects of deepfakes that have been researched (Yu et al., 2021). They are usually the target for producing deepfakes because they allow the generator to smoothly replace the target’s face with another person’s face to suit the needs of the criminal (Almutairi and Elgibreen, 2022). Complex algorithms are used to track the eyes, nose, mouth, and another face that is used to link the target’s traits with the actor’s motions for a realistic media impression. Also, voice synthesis technology has enabled the development of audio deepfakes, which mimic the target’s pitch, pace, and timbre to improve realism (Almutairi and Elgibreen, 2022). Figure 2 shows a sample deepfakes datasets.

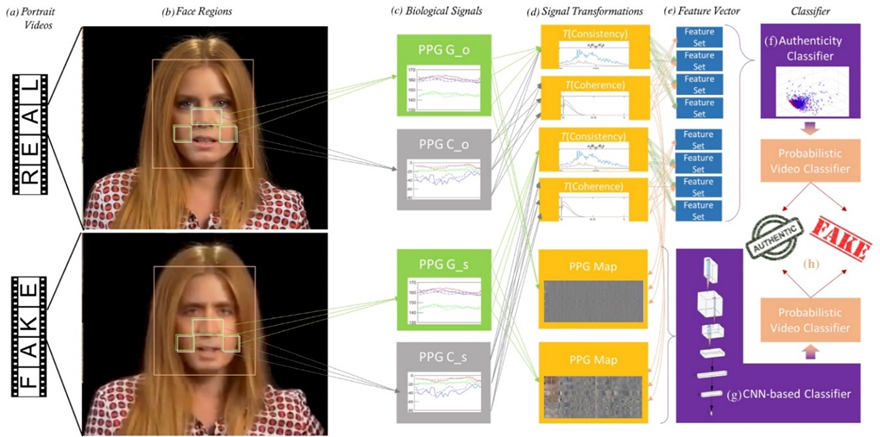

Figure 2: Deepfakes dataset. This sample dataset was used by Ciftci et al. (2020) in the research on biological signals.

One of the most intriguing aspects of deepfake technology is the generator’s ability to learn from the discriminator and gradually produce realistic videos. This machine-learning model can examine enormous datasets, uncover underlying patterns, and build convincing fakes (Mustak et al., 2023). The high processing power of modern technologies enables this iterative approach to take place. It is important to note that deepfake technology uses advanced neural systems (GANs) that require lots of computational power, databases, computer vision, and machine learning knowledge to successfully generate more convincing videos, audio, or photos (Mustak et al., 2023).

Today, many people can access deepfake technology because it is free to anyone who wants it. This is an important asset in altering communications, supporting education, and entertainment in informative and creative ways. Deepfake technology has become popular because it is used to spread misinformation through generated fake news and explicit content (Chesney and Citron, 2019; Mustak et al., 2023). The liar’s dividend, which describes the situation where people evade liability for authentic audio and video suggestions due to public cynicism, is the underlying motivation for deepfakes (Chesney and Citron, 2019). This means that people cultivate misinformation through deepfakes. For example, a criminal may dismiss video evidence incriminating them in an offense as deepfake. The liar’s dividend increases as more people become aware of the deepfakes, implying that as the public becomes more skeptical toward visual media shared on social media platforms, the onus of denouncing video evidence increases. The next chapter explores the implications of deepfakes in cybersecurity.

Deepfakes in cybersecurity contexts

The development of GANs influences risks and threats arising from the misuse of deepfakes. GANs threaten cybersecurity and individual privacy because they can be used to create fake news, commit fraud, blackmail, and sway public belief (Yu et al., 2021). The fact that deepfake technology makes it easy to create fake media introduces major setbacks for authentication and verification of information technology infrastructure (Yu et al., 2021). This means that deepfakes exacerbate cybersecurity threats because attackers can access and use them to generate fake video or audio recordings of a senior leader in an entity and trick them into disclosing confidential information.

Identity theft

Cybercriminals are the major users of deepfake technology. Their interest is to imitate their targets, influence media, and mislead systems, thus explaining why cybercriminals are employing them increasingly. Among deepfakes’ main cybersecurity violations are identity theft. Deepfakes enable identity theft by allowing cybercriminals to impersonate others (Albahar and Almalk, 2019). Attackers use advanced AI to make films, photos, and audio that resemble a person’s voice or likeness with little data. Financial fraud is notoriously committed by impersonating top company executives. For example, a cybercriminal used deepfake audio of a CEO to falsely obtain at least $243,000 from a company, demonstrating how it is difficult to distinguish between fraud and authentic audio and videos (Raza et al., 2022). Deepfakes are used in phishing and other social engineering attacks, where attackers employ convincing videos or audio calls to get victims to reveal sensitive information or access secured systems (Yu, 2024). Such approaches are particularly effective when their goal is to circumvent voice-based authentication. As a result, deepfakes have evolved to threaten privacy and reputation due to increased impersonation attacks on online meetings, social media, and customer service. The increasing accessibility of deepfake technology remains a major cybersecurity threat, as identity theft and impersonation require robust detection tools.

Business fraud

Deepfake technology can also be used to perpetrate fraudulent transactions. Scammers are increasingly using deepfakes to steal money from people who fall into their trap unknowingly. Attackers impersonate CEOs or finance executives using deepfake voice, video, or images to access critical financial systems or authorize payments (Mustak et al., 2023). A famous example occurred when hackers mimicked a CEO’s voice and initiated a transaction that caused the company financial loss. Deepfake technology lets scammers realistically replicate human voices and appearances to bypass authentication (Yu, 2024). Phishers employ deepfakes to elicit financial or philanthropic donations by creating fake videos or messages. These frauds work well by using deepfakes to make victims less suspicious. Because deepfake content is easy to make and powerful for fraud, new detection methods are needed now.

In some cases, deepfake technology has been used to create sexual graphics for blackmailing and extorting money from their targets. Also, these images or videos can humiliate or expose victims whom they know fear the potential effects of their explicit content on the stability of their social, professional, and marriage relationships (Raza et al., 2022). Because deepfake technologies are easy to use, even non-technical people may create convincing content, worsening the situation.

Disinformation and political manipulation

Additionally, deepfake technology is a powerful force that perpetuates disinformation and political manipulation. Deepfakes can sway public opinion and spread misinformation, endangering democracy, and civilization (Broklyn et al., 2024). Bad actors can use realistic audio or video to make political figures appear in public places, making contentious comments, confessing to crimes, or fuelling division and anarchy contrary to their ideals. Such misinformation can cause public anger, divide communities, and influence elections. For example, some extremist groups employ deepfakes to distort history, spread lies, and damage their opponents. Deepfakes cause confusion and mistrust, which can affect the market standing in the industry (Broklyn et al., 2024; Yu, 2024). Edited political speeches or fake interviews are published to sway public perception. There is a need for better detection techniques, media literacy programs, and international cooperation to manage deepfake technologies.

Undermine biometric security

Cybercriminals can sometimes use deepfake technology to undermine biometric security systems, including facial recognition, voice authentication, and retinal scanning. Attackers could obtain unauthorized access to financial accounts, secure networks, or personal devices by utilizing deepfake voices or faces (Yu, 2024). These attacks can cause massive data breaches and financial losses. A hacker might use a deepfake voice to impersonate an account holder during a phone-based security check. Fake faces can trick facial recognition security systems at banks and businesses (Broklyn et al., 2024). Even the most advanced security systems are threatened by deepfakes, which are increasingly harder to detect. Cybersecurity experts suggest behavioral biometrics, multifactor authentication, and AI-powered synthetic media abnormality detection systems that have also been compromised, highlighting the danger that deepfakes cause.

Sabotage forensic investigations

Deepfakes can sabotage evidence and investigations from the data storage point and undermine forensic and legal investigations by injecting false evidence into criminal or court proceedings, which raises doubts about the authenticity of information for the process (Yu et al., 2021). For example, a doctored video could accuse someone of a crime they did not commit, and deepfake audio may incriminate an individual in a crime by fabricating conversations or admissions. Deepfake evidence may impede government or business investigations, considering that they might lose track of the cases and the danger of liar dividend in applying deepfakes. Considering the implication of deepfakes on cybersecurity, the next chapter explores the real-world cases that have been reported in the mainstream media in different parts of the world.

Real-world case studies of deepfake

Political manipulation

Deepfake technology is applied to create a realistic fake post, which is used as a tool for high-profile scams in businesses and political manipulation. The Russo-Ukrainian War presents an excellent case study for understanding how deepfakes influence democracies and political processes, focusing on the experience of the Ukrainian president and territorial integrity against Russian-state-sponsored hacking groups. This case demonstrates the generation of deepfake videos and how they are distributed through social and mainstream media, pointing out their potential impact on today’s conflicts. The conflict brought to the fore the extensive use of deepfake technology during conflicts as a device for misinformation and disinformation (Twomey et al., 2023). Deepfake videos depict the two governments’ efforts downplaying their values and commitment to the conflict. The presentation of these recordings exemplifies how cybercriminals can excel at causing harm to their adversaries, a perfect case for Ukraine and Russia in this conflict.

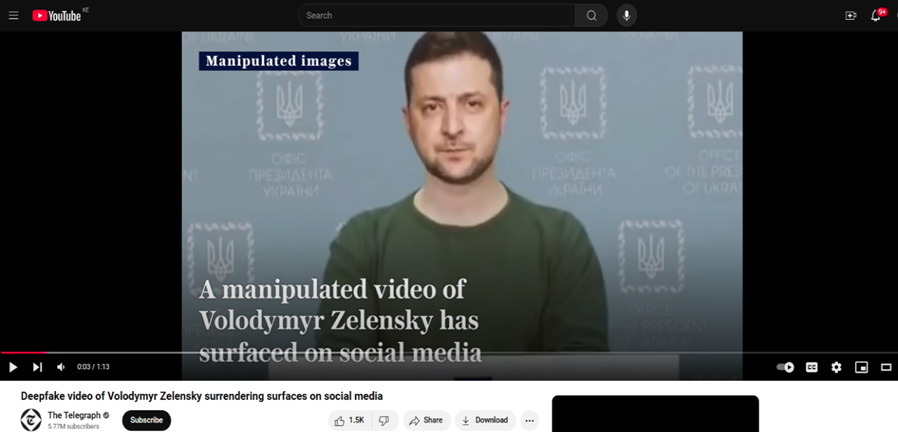

The deepfake that will be explored in this case involves President Volodymyr Zelensky calling on his soldiers to surrender their weapons. The video, which was posted on a Ukrainian news website, presented Zelensky announcing that the war was over, something that did not resonate with most Ukrainians who considered it false. At the time this video was circulating, the ticker on the channel’s live television feed reported similar information – falsely claiming that Ukraine was surrendering. Looking at the video, it is evident that there was improper lip sync, Zelensky’s accent was inaccurate, and his head and voice appeared fake, especially after careful examination. The post elicited comments across the globe. A notable comment was made by a professor of digital media forensics at the University of California, Berkley, Hany Farid, who said, “This is the first one we’ve seen that really got some legs, but I suspect it’s the tip of the iceberg” (Allyn, 2022). The credibility of the video was dealt a bigger blow when President Zelensky responded by saying, “We are defending our land, our children, our families. So, we don’t plan to lay down any arms. Until our victory” (Allyn, 2022). While Zelensky’s response might suggest a potential case of a liar’s dividend, there were glaring inconsistencies in the video that sufficiently sustained his denouncement. The hackers managed to send the video and associated messages extensively across live television broadcasts, including Ukraine 24, the national television, ordered Ukrainians to stop fighting and surrender their weapons. The social media played an important role in amplifying this deepfake. Russia-based VKontakte extensively spread the news.

Figure 3: The Manipulated Video of President Zelensky in February 2022. The video is obtained from the Telegraph Channel on YouTube. The link to the video is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X17yrEV5sl4

Similarly, another case involves developing deepfakes that targeted the political process and the management of the 2023 voting in Slovakia. Manipulated deepfake videos were used to disseminate specifically pro-Russian political information; the content interfered with opponents of Robert Fico, who was later elected prime minister. They were shared through Telegram channels and other encrypted messaging platforms, presenting the opposition figures in a negative way that deepened already existing political rifts. The latter channeled this digital misinformation during Fico’s campaign, and some voters explained that deepfakes influence their decisions based on the credibility of other influential personalities (HKS Misinformation Review, 2023). This case shows that using deepfakes as material for misinformation can go viral and even impact election outcomes, even if the target is not endorsing the videos or the messages.

Business email compromise

Business email compromise (BEC), commonly known as CEO fraud affects an estimated 400 corporates daily. Throughout the globe, CEO fraud poses a major challenge to companies – SMEs and established corporations. In one of the most famous cases in 2019, the scammers attacked a British energy company. They used deepfake audio to pretend to be the CEO of the parent organization of the firm in Germany. The criminal asked the CEO to wire $ 243,000 to Hungary for payment to a supplier with a fake and urgent payment demand (Raza et al., 2022). The CEO, who considered the received call credible, agreed with the request, only to find out that transferring money was the idea of a fraudster. Like most emerging technologies, deepfake voice poses a present danger to corporate information security, as it empowers fraudsters to circumvent voice recognition mechanisms (Yu et al., 2024). This is because the technology used to make the audio and video content look so real that it makes people take actions they would typically not take if they gave it a second thought (Yu et al., 2024).

Adding to the concerns about deepfake manipulation, fraud in Baotou, China, involved using fake video calls. In this case, the fraudster applied a deepfake video of a close friend of the targeted person and asked for about $600,000. Since the victim thought, he was talking to his friend, he agreed to the scammer’s request. Many of the stolen funds were recovered, and, as with the Hatim Erler brothers, the scam exposed people to severe risks due to deepfakes. Such examples can be referred to in this case of the study since personal relations may be used for manipulating individuals by extorting money from them under the guise of close associates, mainly when digital technology is used to imitate such individuals (Economic Times, 2023).

Implications of the case study

The application of deepfake technology in the production of hyper-realistic media poses significant implications for politics and business. The deepfake depicting President Zelensky ordering his military to retreat demonstrates how malicious forces can use these videos to propagate their agenda. It exposes how videos of politicians can easily be manipulated to hoodwink the public. At the same time, the effect of deepfakes in the corporate sector is gross. They demonstrate how fraudsters can alter publicly available images and videos of CEOs to perpetrate crime. Considering the danger of deepfakes in society, it is necessary to deploy appropriate methods to detect them before they cause harm, such as political instability and financial loss. The next chapter explores the different methods that can be used to detect deepfakes.

Deepfake detection methods

Deepfake prediction (DFP) approach

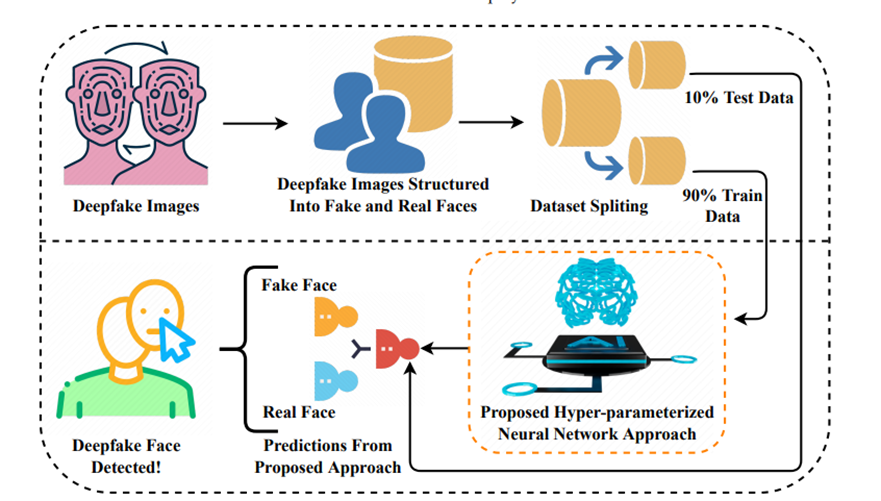

Different methods can be used to detect deepfakes. Today, AI-based technology has become popular. Raza et al. (2022) proposed a “novel deep learning approach for deepfake image detection,” which they call deepfake predictor (DFP). The model is based on VGG16 and convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, indicating that the model is a combination of VGG16 architecture that is integrated with CNN layers to boost performance. These capabilities include pooling layers to reduce dimensionality, dropout layers applied in mitigating overfitting, and relatively dense layers to enhance prediction. The hybrid system can make highly precise predictions on unseen data to help detect fake and real faces in use. The input images, both real and fake, are passed through the VGG16, which is a pre-trained neural network used in detecting images and extracting features. The obtained features are refined through the CNN layers that are fully integrated to analyze and classify the images as either fake or real.

Figure 4: Deepfake prediction methodology. The model method was proposed by Raza et al. (2022). DFP approach is fully hyper-parametrized, yielding the best accuracy score.

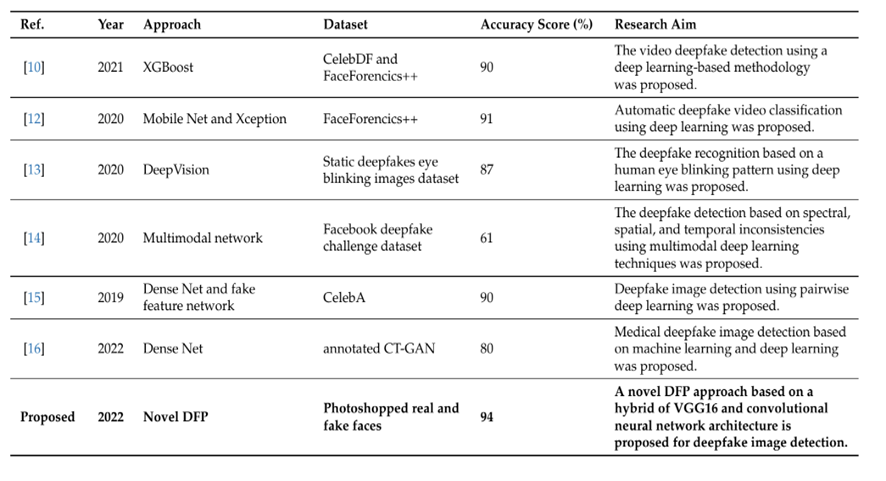

Another important component of the CNN layers is that an output layer, considered the output neuron with a sigmoid activation function, fundamentally predicts the likelihood of an image being fake. The proposed DFP is designed to be optimized by the Adam optimizer, a binary cross-entropy loss function, and sigmoid activation in the output layer. In their experiment, Raza et al. (2022) determined the feasibility of the model at 94% accuracy, with a 94% F1 score on unseen test data. The loss score was also minimal at a paltry 0.2%, suggesting that the model is robust in detecting deepfake images. Thus, the model can be applied in detecting deepfakes because it is generally the most efficient, considering that it has a reduced computational complexity compared to other models like Xception. DFP can also be applied in real-world cybersecurity contexts to reduce vulnerabilities related to blackmail and identity theft. Raza et al. (2022) summarized the comparison between the noble DFP and other detection methods that used unique datasets, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Comparison of different detection methods. The list of deepfake detection methodologies is adapted from Raza et al. (2022).

Biological Signal-based Methods

The biological signal-based methods can be used to detect deepfakes because deepfake videos do not depict accurate human mannerisms, such as blinking, eyebrow movements, or even natural stares. These temporal clues are essential in discriminating original videos from fake ones. Scientists have trained patterns that can pick out irregular blinks in the eyes or movements of the face, which are associated with deepfakes. For example, the neural network model, long-term recurrent CNN (LRCN), was developed to differentiate between open and closed eyes in a video. It determines the blink frequency by cropping the surrounding rectangular regions of the eye into a new pattern of input frames (Yu et al., 2021). Usually, the cropped patterns are fed through the LRCN model to obtain temporal dependencies. The extraction module applies VGG16 to extract the discriminative features from the eye region of the input video. The next step involves passing through sequence learning with the help of execution by the RNN model. In the final stage, a connected layer determines the likelihood of the eye being open or closed, which is then used to calculate the frequency of eye blinks (Yu et al., 2021).

Figure 5: Biological signal analysis. It involves extracting biological signals from face regions of authentic and fake images/ video pairs, and applying transformations to determine spatial coherence and temporal consistency, capturing signal characteristics in feature sets. Adapted from Ciftci et al. (2020).

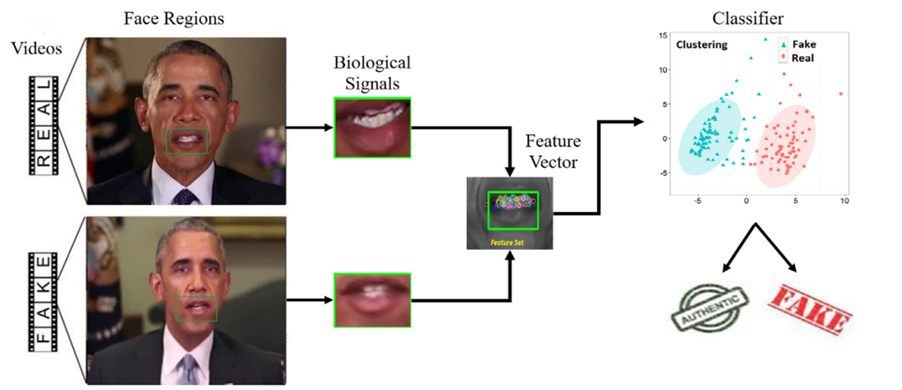

Physiological signals are also being used more to discern fake videos. These cues are placed on identifying fresh shifts in the body movements that are nearly impossible for deepfake algorithms to copy accurately. AI-based systems can analyze these physiological signs that are not discernible to decide whether a video is real or fake. These models scrutinize everything from how often skin color changes during dictation to any facial developments because of talking, which is an excellent resource against deepfakes. Figure 6 shows a detection methodology that uses mouth movement.

Figure 6: Biological signal analysis. The methodology was proposed by Elhassan et al. (2022) in their study where they investigated mouth movements and transfer learning.

Overview of Other Detection Methods

Other approaches to detecting deepfakes include general networks, temporal consistency, visual artifacts, and camera fingerprints (Yu et al., 2021). Table 2 below compares the various methods used to detect deepfakes. General network approaches treat detection as a frame-level classification task accomplished by CNNs. The trained network is applied to predict all frames of the video extracted from a deepfake. The predictions are determined by calculating the mean on the neural networks, indicating that their precision depends on the neural networks under use. This method is limited by its ability to overfit on specific datasets. The temporal consistency, such as the CNN-RNN, examines the time continuity in a deepfake video. This method derives from the fact that autoencoders are unable to remember previously generated faces (that are generated in multi-frames in videos (Yu et al., 2021). The absence of this temporal awareness contributes to anomalies that suggest the presence of deepfake. An end-to-end trainable recurrent deepfake video detection system, based on convolutional long short-term memory (LSTM), is used to define the sequences of the video frames, and the CNN is applied to extract the frame feature while LSTM analyzes the frame (Yu et al., 2021). The next chapter explores various strategies to mitigate deepfakes.

| Detection method | Strengths | Weakness | Application |

| General Networks | Highly adaptable to various types of deepfakes; effective at recognizing patterns in data. | Requires large datasets for training; computationally intensive. | Identifying manipulated videos/images across social media. |

| Temporal Consistency | Exploits the temporal dimension; effective for video deepfakes. | Struggles with single-frame analysis; requires computational resources for time-series analysis. | Detecting altered facial movements in videos. |

| Visual Artifacts | Effective against low-quality deepfakes; easy to implement. | May fail against high-quality or well-trained deepfakes. | Identifying lighting inconsistencies in face-swapped images. |

| Camera Fingerprints | Effective at detecting source manipulation; works well on high-quality, uncompressed media. | Limited by quality requires access to camera-specific information. | Authenticating original versus altered camera footage. |

| Biological Signal-Based | Exploits natural, involuntary signals difficult to replicate; strong against face manipulations. | Limited to facial deepfakes; requires visible biological features in the video | Detecting faked heart rate patterns in manipulated interview footage. |

Table 2: Comparison of strengths and weaknesses of the guiding principle.

Mitigating strategies to combat deepfake threats

Blockchain technology

Mitigating the threats posed by deepfakes requires deploying blockchain technology to verify them and delete them from the source. Blockchain technology can also be used to verify content to combat the creation and spread of deepfakes. The immutable consensus that the distributed blockchain technology guarantees can enable users to determine the point of generated and where the distribution began (Broklyn et al., 2024). This approach can be highly effective in preserving the purity of media shared through the Net since once data gets on the WEB, blockchain makes the information hard to alter. Popular internet sites such as YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook use blockchain systems along with metadata required to prove the originality of an audio or video. This would form a checklist to help authenticate the public media before being released to counter deep fake sensationalism.

Government regulations

The government can also introduce strong laws to mitigate against the consequences of deepfakes and, in doing so, discourage their use. Deepfake is gradually becoming dangerous, and national governments are just beginning to realize this and are creating legislation to guard the public against deepfake (Birrer and Just, 2024). For example, in 2018, the United States signed the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, which makes deepfakes a criminal offense to fraud, harass, or defame individuals using deepfakes. Similarly, the present legal efforts in countries like China and India entail translating the strategies entailing the control of the production and distribution of deepfake political news (Birrer and Just, 2024). It is becoming essential to create an accountability mechanism for individuals who deliberately create such adverse deepfake effects, particularly where it can assure the distribution of fake news with the intent of gaining financially, manipulating the outcome of an election, and or using it to harass through cyberbullying.

However, there are gains to be made from seizing the ramp, where the rate of technological change is steep. So, if the technology becomes even more sophisticated and efficient, legal provisions must also be modified. In addition to criminalization, governments should understand how to pressure such technology companies to make digital platforms fully responsible for moderating the spread of deepfakes, especially those that could compromise the public good, stability, and sustainability (Broklyn et al., 2024). Tech giants such as Facebook and Google and police services can work together to detect those who use deepfake technology to perpetrate fraud.

Awareness creation and public sensitization

Moreover, awareness creation and sensitization campaigns can mitigate the creation and spread of deepfakes. The other crucial approach suggested is increasing people’s ability to recognize deepfakes and their dangers. In most cases, many people who consume deepfake information do not know that media is manipulative through inaccurate information. Some ways the public can be educated include informing the public on occasions where one can easily abuse a situation, how it can be viewed, and whether the firing squad was fake (Birrer and Just, 2024). Even before one shares a specific video, there is a way of checking whether it is fake. The European Union has been raising awareness and funding projects like the DeepTrace that create awareness of deepfakes and improve detection technologies. The subject should be integrated into schools and universities to ensure youth can analyze the media for authenticity. These strategies should be supported by social media platforms that must raise users’ digital awareness. The risk of exposure to dangerous media could be reduced when social websites provide warnings about other deepfake content and assist in fact-checking efforts. The implementation of these measures has implications for ethical issues and global perspectives. The next chapter explores these ethical and global issues associated with deepfakes.

Ethical and Global Perspectives

Public trust

Deepfake technology raises significant issues that touch on principles of public trust. The growth and distribution of deepfakes eroded public confidence in media and digital communication. Today, it is not easy to tell whether the videos available on social media platforms are real or just fabrications designed to achieve the creator’s ulterior motive (Vaccari and Chadwick, 2020). They are pervasive, and people who are not familiar with detecting deepfakes cannot tell if they are fake or real. For example, such challenges pose major setbacks to legitimate judicial processes that may require credible information to arbitrate. Criminals who have been reliably accused of crimes that are adequately backed by evidence availed before a competent court of law can dismiss audio-visual evidence as merely a fabrication intended to harm their reputation. Such cases raise skepticism in people, and the chance that people will admit their ills is indeterminate (Vaccari and Chadwick, 2020). For example, even criminals can discredit genuinely collected evidence by claiming it is another deepfake in circulation. In light of these issues, it is necessary to develop appropriate measures to mitigate the spread of malicious deepfakes to protect corporates from financial loss and bolster the stability of democracies by reducing political manipulation.

Freedom of expression

The advancement in deepfake technology affects people’s rights to freedom of expression. For example, the government’s attempts to regulate the spread of deepfakes through regulatory measures often infringe on people’s freedom of expression and creativity, as they are barred from expressing their art (Hu and Liu, 2024). This means that individuals who want to demonstrate their skills through deepfake technology cannot do so freely, fearing criminalization and prosecution. For instance, in China, regulations on AI have been considered to violate innovators’ freedom of expression. In some cases, overly strict controls could suppress innovative applications of deepfake technology in art, education, and entertainment (Hu and Liu, 2024). These challenges necessitate adopting a balanced approach where there are appropriate measures to distinguish between the malicious use of deepfake for political manipulation or business fraud.

Global perspectives on deepfakes

Different jurisdictions are considering the consequences of deepfakes in their communities and corporations and are developing suitable mitigation measures. For example, in the United States, existing fraud and defamation laws are being used to prosecute adverse applications of deepfake technologies. These regulations are not effective because they are shallow and do not cover all aspects of deepfake technology. Notwithstanding, there are also state-level regulations that apply to the use of deepfake technology, especially regarding the creation of non-consensual explicit content (Alfiani and Santiago, 2024). The major setback to the operationalization of these guidelines, however, is American values of promoting innovation. The prevailing belief is that the United States’ commitment to being the leading technological hub cannot be limited by any regulation, including those that address the usage of deepfake technology. This is not the case in the European Union, where there are comprehensive regulatory frameworks guiding the use of deepfake technology. For example, the Digital Service Act (DSA) has a specific provision dedicated to addressing GAN-generated content – video, image, and audio (Alfiani and Santiago, 2024). It aims to avert illegal activities online and the spread of disinformation that resonates with a commitment to regulating the malicious use of deepfake technology. These regulations are strengthened by the AI Act, which was formulated to shape Europe’s digital future (Alfiani and Santiago, 2024). Its main objective is to ensure that all AI-generated content – video and audio – is identifiable.

Regulations and legislative acts establish the legal and ethical framework that curbs the malicious production and use of deepfakes. Different jurisdictions have regulations to curtail the risk of deepfakes. However, there are undercutting regulatory frameworks that are essential in averting risk. For example, the US and China have adopted legislation to target the misuse of deepfakes, such as identity theft, financial fraud, and disinformation. Ethical standards for AI use have been widely published worldwide as an efficient measure to combat risks that might emerge from creating malicious deepfakes (Hu and Liu, 2024). At the same time, social media platform accountability has become a core tenet of regulatory framework for corporations such as Facebook and Twitter. Objectively, these corporations must implement robust systems to detect malicious activities, including deepfakes, before their consequences become evident (Hu and Liu, 2024). Deepfake risks continue to present significant issues, especially with advancements in AI technology. International regulatory frameworks have been implemented to address the cross-border challenges associated with deepfake.

Overall, while prevention is an advanced measure to combat risks, regulations establish the ethical and legal framework for producing and deploying deepfakes. The combined value of these measures is based on their ability to create a multi-layered defense system. Prevention limits the technical feasibility of generating and spreading deepfakes for malicious interests. Regulatory frameworks deter actors from exploiting these technologies for malicious gains by emphasizing the legal consequences of a deliberate breach. Therefore, the attempts to combat deepfakes, including their impacts on cybersecurity, require the adoption of appropriate prevention and regulatory measures.

Ethical issues

The challenges associated with deepfakes raise essential ethical issues that users, corporations, and the government should consider amidst its growth in popularity. Deepfakes engrave the issue of consent and autonomy. The main challenge relates to the lack of informed consent whenever criminals create malicious videos and audio that they intend to use to manipulate their target (Tuysuz and Kılıç, 2023). Individuals whose images or videos are used to generate deepfakes often ask about their autonomy over digital identity and consent. Other ethical issues that need consideration are the ethics of digital content, manipulation of identity, and digital agency. These ethical considerations involve misinformation and loss of trust, spread of false information, information integrity, and digital deception (Tuysuz and Kılıç, 2023). Accordingly, it is essential that the use of deepfakes must be informed by the impact on society, moral responsibility, and ethical use guidelines, which require strict compliance with an ethical framework.

Conclusion and recommendation

Deepfake technology rapidly evolves to create cybersecurity challenges to digital communication, institutional trust, and social relationships. The study has explored how advancements in deepfakes have affected business connections and democracies. Powered by GANs, a powerful AI machine learning architecture, deepfakes can potentially create hyper-realistic media that people cannot easily discern from real images or videos. The ability of GANs to generate these synthetic media that people cannot easily classify as unreal is a major challenge to policymakers, individuals targeted with fraud, and corporations that navigate CEO fraud – identity theft and financial fraud. Deepfakes have also been at the center of swaying public opinion, undermining political systems, and perpetuating chaos during conflicts. The manipulated video of President Zelensky calling on the military to withdraw combat clearly demonstrates how deepfakes can be abused in a conflict. This means that advancement in deepfakes increases vulnerabilities to the integrity of biometric security systems, disinformation campaigns, impersonation, and potential interference with legal processes and forensic investigations. Different approaches can be used to detect deepfakes: AI-based and biological options.

These challenges necessitate the implementation of comprehensive mitigation measures. These strategies could include technology solutions using advanced AI-based detection algorithms, blockchain verification technologies, and operationalization of complex authentication tools. Legal and regulatory frameworks can also provide critical insights into mitigating deepfakes. Adopting legislation that criminalizes the creation of malicious deepfakes, fostering international cooperation to address cross-border challenges in managing the risk landscape, and promoting accountability mechanisms for digital platforms are some of the essential regulatory strategies that can address the increasing cases of malicious deepfakes. Given the availability and easy access to deepfake technologies, it is essential to promote public awareness and education programs to bolster the ability to recognize fraudulent videos, audio, and images.

These strategic alternatives require prioritizing media literacy programs, digital awareness campaigns, and integration of deepfake awareness into existing education curricula in schools. These approaches will bolster the public’s knowledge and utilization of deepfakes. A multi-faceted approach can offer more robust mitigation considering the complex challenges deepfakes pose to businesses through financial loss and governments through political manipulation. This approach emphasizes the collaboration of different stakeholders involved in development, distribution, and utilization and the creation of legal and regulatory measures that underpin the challenges deepfake causes in society.

Summary

Deepfake technology is both a transformative and dangerous innovation. This paper examines the diverse impacts of deepfake technology on cybersecurity by discussing its capabilities, real-world applications, and threats that everyone should pay attention to and possibly brainstorm solutions. Media generated by GANs are considered hyper-realistic because they are difficult to discern from real photos. The iterative process of GANs during image generation effectively culminates in media with striking accuracy. While deepfakes are a good innovation, criminals have majorly exploited them to achieve their malicious motives. Deepfake technology is available through open-source platforms such as GitHub. This has democratized its usage for creative and innovation pursuits, as well as malicious exploitation. In most cases, it has turned out that deepfake technology has been used by criminals to steal information and pressure businesses into losing finances. This study has explored how deepfake technology has been used in the Russo-Ukrainian War, with the most striking example being a political manipulation targeting President Zelensky. The case demonstrated how deepfake could be used to spread disinformation.

The consequences of deepfake technology necessitate developing detection methods. Methods such as Convolutional neural networks, temporary consistency checks, and biological signals have demonstrated viability. Also, blockchain solutions can be essential in verifying the authenticity and background check on the deepfake. Considering the ethical, social, economic, and political consequences of deepfakes, it is necessary to adopt advanced detection technologies with robust legal frameworks to ensure accountability of social media platforms where most of the social engineering occurs. Education and public awareness campaigns can also help empower people to identify deepfakes and resist misleading media. People must implement these conscious efforts while upholding ethics, which will support balancing innovation with trust and privacy.

List of references

Albahar, M. and Almalki, J., 2019. Deepfakes: Threats and countermeasures systematic review. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 97(22), pp.3242-3250. https://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol97No22/7Vol97No22.pdf

Alfiani, F.R.N. and Santiago, F., 2024. A Comparative Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Regulatory Law in Asia, Europe, and America. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 204, p. 07006). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202420407006

Almutairi, Z. and Elgibreen, H., 2022. A Review of Modern Audio Deepfake Detection Methods: Challenges and Future Directions. Algorithms, 15(5), pp.155; https://doi.org/10.3390/a15050155

Allyn, B., 2022, March 16. Deepfake video of Zelenskyy could be ‘tip of the iceberg’ in info war, experts warn [Online]. NPR Available from https://www.npr.org/2022/03/16/1087062648/deepfake-video-zelenskyy-experts-war-manipulation-ukraine-russia [Accessed 4 December 2020].

Birrer, A. and Just, N., 2024. What we know and don’t know about deepfakes: An investigation into the state of the research and regulatory landscape. new media and society, p.14614448241253138. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241253138

Broklyn, P., Egon, A. and Shad, R., 2024. Deepfakes and cybersecurity: Detection and mitigation. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4904874 [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Chesney, R. and Citron, D. K., 2019. Deepfakes and the new disinformation war: The coming age of post-truth geopolitics. Foreign Affairs, 98(1), pp.147-155. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2018-12-11/deepfakes-and-new-disinformation-war. [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Ciftci, U.A., Demir, I. and Yin, L., 2020. Fakecatcher: Detection of synthetic portrait videos using biological signals. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3009287

Economic Times, 2023. May 22. ‘Deepfake’ scam in China fans worries over AI-driven fraud [Online]. Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/deepfake-scam-in-china-fans-worries-over-ai-driven-fraud/articleshow/100421546.cms?from=mdr. [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Elhassan, A., Al-Fawa’reh, M., Jafar, M.T., Ababneh, M. and Jafar, S.T., 2022. DFT-MF: Enhanced deepfake detection using mouth movement and transfer learning. SoftwareX, 19, p.101115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2022.101115

HKS Misinformation Review, 2023. Beyond the deepfake hype: AI, democracy, and “the Slovak case” [Online]. MIS Info Review. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/beyond-the-deepfake-hype-ai-democracy-and-the-slovak-case/ [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Hu, Q. and Liu, W., 2024. The Regulation of Artificial Intelligence in China.” In 2024 3rd International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities and Arts. Atlantis Press, pp. 681-689. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-38476-259-0_71

Mirsky, Y. and Lee, W., 2021. The creation and detection of deepfakes: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(1), pp.1–41. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.11138

Mustak, M., Salminen, J., Mäntymäki, M., Rahman, A. and Dwivedi, Y. K., 2023. Deepfakes: Deceptions, mitigations, and opportunities. Journal of Business Research, 154, pp.113368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113368

Raza, A., Munir, K. and Almutairi, M., 2022. A novel deep learning approach for deepfake image detection. Applied Sciences, 12(19), pp.9820. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199820

Seng, L. N., Mamat, N., Abas, H. and Ali, W., 2024. AI integrity solutions for deepfake identification and prevention. Open International Journal of Informatics, 12(1), pp.35-46. https://doi.org/10.11113/oiji2024.12n1.297

Twomey, J., Ching, D., Aylett, M.P., Quayle, M., Linehan, C. and Murphy, G., 2023. Do deepfake videos undermine our epistemic trust? A thematic analysis of tweets that discuss deepfakes in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Plos one, 18(10), p.e0291668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291668

Tuysuz, M.K. and Kılıç, A., 2023. Analysing the Legal and Ethical Considerations of Deepfake Technology. Interdisciplinary Studies in Society, Law, and Politics, 2(2), pp.4-10. https://doi.org/10.61838/kman.isslp.2.2.2

Vaccari, C. and Chadwick, A., 2020. Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social media+ Society, 6(1), p.2056305120903408. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Yu, G. A., 2024. Deepfakes as a cybersecurity threat. Право и практика, (2), pp.119-123. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/deepfakes-as-a-cybersecurity-threat

Yu, P., Xia, Z., Fei, J. and Lu, Y., 2021. A survey on deepfake video detection. Iet Biometrics, 10(6), pp.607-624. https://doi.org/10.1049/bme2